Nothing lasts forever. Even the longest, the most glittering reign must come to an end someday.

~ Edward Greyhaven Francis Urquhart, House of Cards (1990)

The date is May 3, 1979, and Art Garfunkel currently reigns supreme on the UK singles charts, holding the No. 1 spot for the fourth straight week with “Bright Eyes,” written by Mike Batt for the rather polarising yet broadly critically-acclaimed animated adaptation of Richard Adams’ Watership Down. It will go on to be the best-selling single of the year.

Meanwhile in the land of cinema, the big release of the week is Last Embrace starring Roy Scheider and Janet Margolin, a neo-noir movie which I have neither seen nor heard of. Judging by its only pulling in about $1.5 million at the box office, and only having about 6,000 ratings on IMDb, it seems I’m not the only one, but it’s still notable as an early directorial effort from one Jonathan Demme, who would go on to bigger and better things with films like Stop Making Sense, The Silence of the Lambs and Philadelphia.

Doctor Who is currently off the air, having concluded its sixteenth season in late February with the broadcast of the final part of Bob Baker and Dave Martin’s The Armageddon Factor. Mary Tamm and John Leeson have both deigned to bid farewell to the programme, to be replaced by Lalla Ward and David Brierly respectively.

Behind the scenes, Ward, Tom Baker, and guest actor Tom Chadbon have just wrapped up a four-day location shoot in Paris for City of Death, drawing the series’ first ever overseas sojourn to a close. On the same day, script editor Douglas Adams ended up making an unexpected appearance in the French capital, having arrived to discuss the forthcoming production of Destiny of the Daleks with producer Graham Williams. Adams being Adams, this apparently ended up morphing into an epic continental pub crawl that saw the two men wind up in West Germany, before finally returning home to the UK on the 4th.

I mention all of this mostly to make one crucial point: If you ever wind up with a hangover in the course of your life, no matter how nightmarishly painful it may be, you can at least be relatively secure in the knowledge that you will probably not return home to find that the country is now being run by Margaret Thatcher. Indeed, it may well be that there is no more sobering realisation under the sun.

And so we’re presented with one of those surreally serendipitous occasions in which a small, insignificant moment like an impromptu pub crawl organised by two members of the Doctor Who production staff actually ends up coinciding perfectly with one of the defining shifts in British culture, a juxtaposition so utterly beautiful that even the most fanciful of poets could never hope to dream up its like if you gave them a million years.

With the benefit of hindsight though, we probably shouldn’t be at all surprised that Thatcher ended up carrying the Conservatives to victory in 1979. Whatever else she may have been – and make no mistake, Margaret Thatcher was many, many things, all of them quite terrible in nature – she always possessed a keen understanding of the ways in which she could use the media to her own personal advantage.

There are all manner of examples we could bring up here, from her ability to mobilise the virulent racism and homophobia of groups like the National Front or Mary Whitehouse’s National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association (which we actually already discussed back in Dave Stone’s Burning Heart), to her truly groundbreaking conclusion that Enoch Powell’s grotesquely xenophobic “Rivers of Blood” speech had a good, worthwhile message at its core that was ultimately just the victim of poor phrasing on the Shadow Minister’s part.

All of these would be worthwhile topics, but it’s perhaps most illuminating to stick to the familiar territory surrounding the 1979 general election. When it emerged that the centrepiece of the Conservatives’ “Labour Isn’t Working” campaign was the product of photographic manipulation, deliberately playing up the desired image of a dole queue in spite of a measly twenty volunteers turning up for the photoshoot on the day, Chancellor Denis Healey railed against the advertisement in the House of Commons, accusing Saatchi and Saatchi and their newfound Whitehall clients of “selling politics like soap-powder.” For all that the accusation may have stuck, however, it seemed that the electorate were more than willing to buy the Tories’ product of choice.

Against the disturbingly well-oiled media machine of Margaret Thatcher, then, James Callaghan was always going to come up short. Truthful or not, the notion of Callaghan as a weak, ineffectual and out-of-touch Prime Minister who failed to adequately respond to the pressures of the so-called Winter of Discontent would prove to be the enduring image of his premiership in the popular consciousness, spurred on by a gleeful national press with brazen misquotes like the infamous “Crisis? What crisis?” headline with which The Sun ran in their coverage of the PM’s first press conference after returning from a diplomatic function in the Caribbean.

In light of this resounding defeat, then, Labour would enter a prolonged and painful hangover to rival the best efforts of Adams and Williams. Callaghan would stay on as party leader for the next seventeen months, before being succeeded by his former Deputy, Michael Foot.

Facing a schism from a number of prominent moderate Labour MPs, who went on to form the Social Democratic Party, Foot’s more vehemently left-wing policies ultimately ended up alienating substantial tracts of the party’s voting base, and the 1983 general election would see Labour lose sixty seats and more than three million votes, recording their worst electoral performance since the turbulent days of Ramsay MacDonald and his National Government in the early 1930s.

After Foot stepped down – pun very much intended – the mantle of Labour leadership was taken up by Neil Kinnock, who began to more firmly steer the party away from the more militant left-wing politics that were already coming to be viewed as having been poisonous to his immediate predecessor’s bid for the Prime Ministership, going so far as to vociferously oppose the tactics of National Union of Mineworkers leader Arthur Scargill in the 1984-85 miners’ strike.

Despite these efforts to make a clean break with the unfavourable image that Labour had built up in the minds of many, Kinnock remained unable to oust the Conservatives from the top of the electoral pile, even as an increasingly divisive Thatcher saw herself voted out by her party colleagues in favour of Chancellor John Major, whose premiership was almost immediately dogged by the looming spectre of recession and widespread predictions that the 1992 general election would result in a narrow Labour majority or, at the very least, a hung parliament.

Following Labour’s fourth consecutive defeat, the party saw yet another contentious leadership change, as Shadow Chancellor John Smith was elected as Kinnock’s successor. Although the party’s approval ratings benefitted significantly from public disillusionment with the Conservatives’ leadership in the wake of a string of high-profile scandals, Smith’s more circumspect and cautious approach to reforming the party when compared with Kinnock ended up causing internal friction between himself and members of his Shadow Cabinet, with the most vocal critics being a rapidly-rising pair of Shadow Ministers by the name of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

And then, in May 1994, at the age of 55, Smith suffered a fatal heart attack in his London apartment, having given a speech at the Park Lane Hotel just the previous night. The subsequent leadership election some two months later saw Blair triumph over both John Prescott and interim Labour leader Margaret Beckett. For those of you keeping track on the Virgin Books timeline, this means that we’ve now caught up to around the release of Blood Harvest and Goth Opera. In fact, the novels were actually published on the exact same day as the fateful leadership election, because history apparently feels serendipity to be too neat a concept to not get trotted out a second time.

At the annual Labour Party Conference that October, Blair graced the world with the first inklings of his bold new vision for Labour in a piece of oratorical sloganeering that would effectively go on to shape the party’s policy for more than a decade: “New Labour, new Britain.” According to Welsh historian Kenneth O. Morgan, Blair’s speech used the word “new” a total of thirty-seven times, while the party’s accompanying draft manifesto for the forthcoming general election managed an even more impressive count of 107.

Which brings us, finally, to the present day, or the nearest thing for our current purposes. The date is April 18, 1997, a little under two weeks out from the general election, and the number one single is R. Kelly’s “I Believe I Can Fly,” given a boost by virtue of its appearance in the smash feature-length Nike commercial, Space Jam, which as far as the “Films Featuring Animated Rabbits” spectrum goes, is pretty much the exact polar opposite of Watership Down. This, incidentally, almost certainly makes for a most grimly entertaining double feature to bookend the pop cultural experience of the Tory years, if you’re interested in such things.

(If you’re understandably troubled by Kelly’s chart position here given subsequent revelations about his status as a truly monstrous individual in years to come, it might also bear noting that the week of the election will see his three-week shot at UK chart dominance ended by none other than Michael Jackson, making this something of an uncomfortable time to look back on, to say the least.)

Cinema-wise, three films see a wide theatrical release in the United States, and all land with a loud and unmistakable splat at the box office. It’s hard to see why, really, as a cinematic adaptation of McHale’s Navy from the man who brought you Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers: The Movie does sound like ever so enticing an offer, to say nothing of mid-tier Joe Pesci vehicle and unabashed Pulp Fiction imitator 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag.

This same week also saw the release of Lynne Stopkewich’s Kissed, a movie which tackles such whimsical topics as female sexual repression and necrophilia, and whose failure to ignite much buzz among audiences is consequently rather more explicable. Nevertheless, it does apparently feature the use of the Aquanettas’ “Beach Party,” which I only really mention because I actually quite like the Aquanettas, and consider them one of the more underrated gems to be found amidst the post-punk and alternative rock scene of the early 1990s. Consider that a last-minute Dale’s Ramblings recommendation, just for the hell of it.

In the United Kingdom, of course, we find ourselves faced with yet another general election whose outcome seems all but assured. The slim majority enjoyed by Major and the Conservatives at the 1992 election has since been whittled away thanks to a series of resignations and unfavourable by-elections, in an ironic echo of the fate which befell Callaghan some eighteen years earlier.

Being about a decade or so younger than Major, and fifteen years younger than Smith, the forty-three year-old Blair seemed increasingly like the vanguard of an approaching tide of reform that would sweep through the established political order and leave a better, shinier world in its place, with Labour consistently placing ahead in opinion polls in the lead-up to the election. When it comes down to the crunch in about two weeks’ time, the party will ultimately win more than 400 seats in a landslide victory, leaving the Conservatives to mull over their weakest electoral showing in nearly a century.

In other words, what we are on the verge of witnessing here is almost certainly the peak of the so-called “Third Way” school of liberalism, that period of time when both Blair and Clinton were in the ascendant, and the styles of leadership and political reform that they were initially taken to exemplify were setting the tone of political discourse on a wide scale.

(Australia, in a move that won’t exactly help put paid to the tiresome memes about the denizens of the Southern Hemisphere existing upside down, seemingly got things the wrong way around, having spent the 1980s and early 1990s preemptively speed-running through the rise and fall of its own Prime Minister/Treasurer power couple who espoused a Third Way-esque version of Labor Party policies, before handing off to a leader from the opposite party who would stay in power until 2007. Parallels, people, parallels.)

In retrospect, we can see this peak as the fleeting cultural blip that it ultimately turned out to be, and Labour and the British left are largely still falling over themselves in an infighting-riddled effort to decide just how much of a failed experiment “New Labour” was. That it did in fact fail when confronted with problems like the Iraq War, if not well before that, is pretty much inarguable, given just how low Blair’s approval ratings sank in the aftermath of his decision to back the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq, leading to the ignominious resignation which would punctuate the end of his residence in Downing Street.

And at the end of the day, Blair’s fall from electoral grace is a pretty effective microcosm of what the 1990s are really building to, as we repeatedly like to stress on Dale’s Ramblings, since we have principally been concerned with the 1990s as our topic of choice so far. The post-Cold War unipolar moment and the purported end of history in which writers like Charles Krauthammer or Francis Fukuyama so glowingly exulted crashed head-first into the grim realities of 9/11 and the War on Terror. There’s no escaping the shadow that that realisation casts, even when discussing moments that might initially appear to be triumphant in nature.

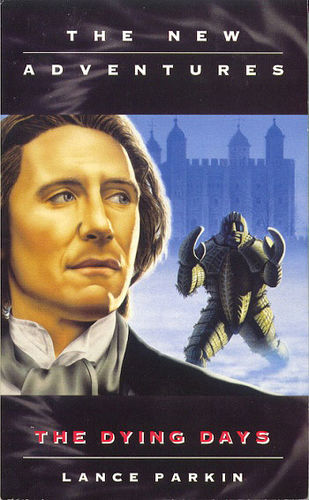

Furthermore, this feeds into the reason I chose to open a review of Lance Parkin’s The Dying Days with about two thousand words attempting to give a whirlwind tour of two decades of British politics. Well, OK, there are a few reasons, but they all kind of boil down to the same thing. First, it is a truth universally acknowledged that any discussion of UK politics from Dale’s Ramblings must inevitably circle around to the subject of Gordon Brown at some point or another.

More importantly, though, this sense of an uncertain transition into an unknowable future hangs over every word of The Dying Days like a funeral shroud – as you might feasibly have expected on the basis of the title alone – tapping into the anxieties of the New Adventures and the United Kingdom as a nation in equal measure. There’s something poetic in the fact that the last NA to feature the Doctor should also be the last novel of the Wilderness Years to be published under a Conservative government, So Vile a Sin notwithstanding.

Indeed, Blair will end up clinging on to power for so long that by the time we reach the end of Dale’s Ramblings as a project – or, at least, as a project chiefly concerned with the business of covering Doctor Who books – with the review of Atom Bomb Blues in December 2005, we will still be dealing with the very same Prime Minister whose arrival seems so imminent at this present moment in April 1997.

This is our first big clue into what exactly The Dying Days is trying to do, title aside, and Parkin is at least candid enough to signpost his intentions from pretty early in the piece, with Benny’s internal admission that she can’t recall the identities of the leaders of either the United Kingdom or the United States, owing to the two countries having both held elections in the nine months before the novel’s opening setting of May 6, 1997.

Taken on its own, this is a seemingly insignificant point, with Parkin himself characterising it as a simple means of covering his bases in the event that it turned out he had made the wrong call in the gap between the novel’s being written and its eventual publication. This, on a basic level, makes perfect sense for what we know of Parkin’s artistic and creative temperament, given what we discussed back in Cold Fusion with regards to his status as one of the novelists most concerned with the explicit historicisation of Doctor Who as a narrative that maps relatively neatly onto real-world cultural and social concerns, even as he often self-deprecatingly admits that such an approach will always have a tendency to run itself up a blind alley of incoherence.

Considering this fact, it’s perhaps telling that, when given the chance to update the novel for the 2003 BBCi re-release, Parkin’s only substantial addition served to tie the story all the more firmly to its era of choice. To quote Bernice Summerfield: The Inside Story:

“Oh, I had the option to change it,” [Parkin] says. “Marc Platt revised Lungbarrow a fair amount. I twiddled a couple of details, corrected a couple of things, but nothing major. The version I had on disc wasn’t the copy-edited version. I copy-edited it myself, so there will be quite a lot of little differences. The major thing I did was add the Spice Girls to the party scene; they didn’t exist when I wrote the book, but it’s difficult to imagine 1997 without them.”

But there is something strange lurking underneath this observation, is there not? The Blairslide was, after all, far from being wholly unpredictable, to the point where even Zamper, published all the way back in August 1995, felt confident enough to drop a passing reference to “Number Ten, Tony’s den.” Ironically enough, I only recalled that particular factoid thanks to having obsessively pored over Parkin’s own AHistory over the years.

Clinton’s victory, admittedly, could have been said to be a marginally less sure bet than Blair’s, with the Democrats having managed the rare feat of losing both the House of Representatives and the Senate in the 1994 midterm elections. Still, the fact that the Republicans ended up selecting the 73-year-old Bob Dole as their presidential hopeful made it hilariously easy for the Democrats to capitalise upon Clinton’s public image as a young, forward-thinking political innovator, riding a booming economy to another resounding victory, with Ross Perot’s third-party candidacy politely managing to prove significantly less of an irritant than it had in 1992.

(In one of those amusing consequences that necessarily comes about when you legally require your presidential candidates to be at least thirty-five years old, Clinton would probably not have been considered particularly youthful by the standards of contemporaneous British politics, being only three years younger than Major, and about five years younger than Liberal Democrat leader Paddy Ashdown.)

All of which is really just a roundabout way of saying that the logic of “attempting to avoid glaring errors in predicting the outcome of two reasonably assured elections” doesn’t really stand up all that well to much scrutiny.

Even if Parkin had somehow ended up being totally wrong in his predictions, it probably couldn’t have been that much more embarrassing than comparable blunders like The Green Death half-seriously positing the possibility of Liberal Party leader Jeremy Thorpe being elevated to the Prime Ministership, or Battlefield predicting that a story apparently set in the late 1990s -around about 1997 by most sources’ reckoning, funnily enough – would see both the continued existence of a unified Czechoslovakia and the presence of a King upon the Sovereign’s Throne.

More to the point, chances were good that it would instead end up more akin to something like Terror of the Zygons fleetingly referencing a female Prime Minister in an obvious tip of the hat to Thatcher, who had only recently succeeded Edward Heath as Conservative Party leader at the time of the story’s original production in early 1975.

No, what’s really going on here is that The Dying Days is thoroughly committing to its positioning at a strange and ambiguous turning point in the intertwining histories of Doctor Who and the United Kingdom. If we read The Dying Days as a document telling of an Ice Warrior invasion in early May 1997 – as A History of the Universe and AHistory would prefer – this ambiguity is puzzling, but it actually fits perfectly if we read it as the sixty-first and final New Adventure to feature the Doctor, published in April of that same year. Because, well, that’s what it is, and that’s exactly how it would have been presented to audiences upon its initial publication.

Central to any turning point worth its salt, however, is a closing down of a particular vision of the future, the erasure of a given possibility and its supersession by something new, and within the text of The Dying Days there is no better example with which to start than that of Edward Greyhaven.

The most noteworthy thing about Greyhaven is that he’s very obviously played by legendary Shakespearean actor Ian Richardson. It is of course true that every Parkin book thus far has included a character modelled on Richardson, to the point where I’ve even enshrined the habit in the form of a semi-recurring and semi-serious recurring feature entitled the “Richardson Report.” Even before you factor in the illustrations from Allan Bednar, the source of inspiration should be clear enough from the moment Greyhaven is introduced as having an “aquiline face,” a descriptor that has already been enshrined, just three novels in, as one of Parkin’s go-to signifiers when introducing a Richardson-based character to the audience.

In the case of The Dying Days though, this resemblance is taken one step further than it was when we talked about Oskar Steinmann in Just War or Admiral Dattani in Cold Fusion. Greyhaven is not just based on Richardson, but on one of the actor’s most famous roles, that of scheming Chief Whip and eventual Prime Minister Francis Urquhart in Andrew Davies’ critically-acclaimed televised adaptations of the House of Cards novels for the BBC.

Urquhart, by definition, is inextricably linked to the identity crisis that arose in the late Thatcher years among the Conservative Party faithful, with the original House of Cards having been written by prominent Tory staffer Michael Dobbs, who was unflatteringly but memorably dubbed “Westminster’s baby-faced hit man” by a 1987 article in The Guardian, and rather more flatteringly dubbed a Life Peer in 2010.

As if to reinforce these connections even further, Thatcher would formally resign from the party leadership just three days after the airing of House of Cards‘ second episode, turning the opening lines of the serial – duly reproduced at the beginning of this review, naturally – into a grim and prescient portent of a Prime Minister’s demise. By the time of The Final Cut‘s airing in November 1995, this portent had become quite literal, opening with a hypothetical depiction of the funeral of the still very much alive Thatcher that so incensed Dobbs that he requested Davies remove his name from the opening credits post-haste.

Greyhaven, appropriately enough for The Dying Days‘ broader points, is a considerably more ambiguous figure when taken in isolation. His political affiliations are never explicitly pinned down, such that you could theoretically choose to read him as either a Conservative or as a Labour MP. Even having the Doctor recognise him as the minister for science from the UNIT days is no big help, given the legendary asterisk which hovers over any attempts to pin down a precise date for any of the stories featuring UNIT.

Even this seems like overstating the case though. As far as Virgin is concerned, the evidence overwhelmingly supports a dating for the UNIT era that places it as being roughly contemporaneous with the time of broadcast for the original Pertwee stories, most prominently in the form of works like Who Killed Kennedy.

Indeed, Parkin even explicitly draws attention to the link between The Dying Days and Who Killed Kennedy, cheekily asserting that the in-universe version of the book caused the government no small measure of embarrassment, suggesting that both James Stevens and David Bishop were subsequently put under surveillance by MI5, and that the publishers of the book were pressured into swearing that they’d never print anything of its like again. So that’d be Virgin, then, and one might almost imagine that “anything of its like” might include any books that purport to tell of the escapades of some mysterious Doctor. Really makes you think, huh?

(As an addendum, to firmly plant my own flag in a particular corner of the UNIT dating debate -which is probably, to be perfectly honest, fundamentally incapable of ever being resolved given the sheer weight of identically weighted and mutually incompatible evidence with which the audience is presented – I do think that the evidence of the Pertwee Era itself supports a contemporary dating, more often than not. It admittedly means accepting a definition of “contemporary” that features accurate historical details like pre-decimal currency in March 1970 existing almost side-by-side with profoundly ahistorical concepts like a fully-fledged British space programme, but this is no more nonsensical than seriously trying to argue, as many fans have over the years, that Sarah Jane Smith is somehow confused as to what year she hails from. Madness comes with the territory in this case.)

Accepting a roughly contemporary dating as a given, then, the inescapable conclusion seems to be that Greyhaven was part of whichever political party was in office in the period spanning roughly from the broadcast of Spearhead from Space in January 1970 to Planet of the Spiders in June 1974. As it happens, this coincides almost exactly with the Conservative government of Edward Heath, which had entered office a day before the final episode of Inferno, and was ousted by Harold Wilson’s reinvigorated Labour government in the gap between Death to the Daleks‘ second and third episodes.

What’s more, a careful inspection of the particulars of the Heath ministry will show that the post of “Minister for Science” – or, more formally, the Secretary of State for Education and Science, the two portfolios having been combined between 1964 and 1992 for reasons that I’m sure made perfectly good sense at the time – was consistently held by none other than Margaret Thatcher herself.

Given Greyhaven’s demonstrable status as an avatar of a bygone era of the Conservative Party, however coy The Dying Days chooses to play it, there’s a sense in which the character’s power-mad attempt to install Xznaal on the British throne – to have him play the King, if you will – serves as nothing so much as a final repudiation of the possible future that Urquhart represented, in which it was at all feasible to imagine that the Conservatives’ Chief Whip could ever hope to eclipse Thatcher’s record as the longest-serving post-war Prime Minister of the twentieth century.

The other important point that Greyhaven serves to establish is the notion that much of The Dying Days is operating off of a deeply symbolic logic, relying on the audience’s awareness of the wider cultural landscape of April 1997 to project a code of meaning onto the novel beyond that which might be present on a purely textual level.

This bleeds through into the treatment of the Brigadier, who is an obvious choice to fill the role of the more well-established and dignified representative of the Pertwee Era, in a way that a guest character like Greyhaven simply can’t ever hope to compete with. Lest this be misconstrued as an accusation that Parkin’s character work is shallow and solely trades on fan nostalgia, I should stress that that’s far from being the case.

I mean, yes, the novel is obviously not short on nostalgic reverence for the character, but that’s very much been enshrined as standard operating procedure for the Brigadier since at least No Future, and if we’re being truly pedantic sticklers we could probably make a case for that strain of thought stretching as far back as Mawdryn Undead and The Five Doctors. In other words, Brigadier Alistair Gordon Lethbridge-Stewart is probably the regular character who feels like the most natural fit for this kind of symbol-based storytelling.

Whatever the underlying discomfort that writers like Paul Cornell might feel about the Pertwee Era exiling the Doctor to Earth and making him a Tory – and the Doctor’s casual recognition of Greyhaven here certainly does nothing to dispel those accusations – it cannot be denied that the Brigadier and Nicholas Courtney are very much an institution in their own right at this stage. Even Cornell himself seems willing to join in the fun, at least if Happy Endings is anything to go by, and it’s no big surprise that The Wedding of River Song would ultimately choose to implicitly pay tribute to Courtney after his passing. The Brigadier possesses an almost larger-than-life status that just about allows you to get by on sticking him into any story of your choosing and trusting that that alone will nudge it into attaining the coveted status of an “event story.”

As, it must be said, kind of happens here. The character is excellent, and as likeable as ever, but it’s not as if there’s much in the way of deep profundity to be mined from his presence, beyond reiterating the whole “UNIT: The Next Generation” feel that we already got from Battlefield, complete with the return of Bambera. Yet The Dying Days, as the last New Adventure, existing in the aftermath of the introspective and moody character work of novels like The Room With No Doors and Lungbarrow, doesn’t really need to do “profound” in order to work; it can instead let loose a little bit and just have fun, placing its money on “solid and dependable,” much like the character of the Brigadier himself.

“Solid and dependable” also serves to characterise the plot of the novel itself. With its focus on a Mars probe gone awry, the involvement of UNIT and some sketchy Prime Ministerial shenanigans, it wouldn’t perhaps be entirely unreasonable to make a few snide comments here about the possibility of Russell T. Davies filing away a few notes for later use in The Christmas Invasion.

More seriously, though, if there’s any similarity it really only stems from the fact that, for the pure iconic spectacle of the thing, you can’t really beat “a massive alien spaceship shows up and hovers over some identifiable landmarks.” It’s probably at least 95% of the reason Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day made more than $800 million at the box office, after all, and Parkin himself quite readily admits to The Dying Days owing something of an artistic debt to that cornerstone of 1990s disaster cinema.

In turn, The Christmas Invasion might be thought to include a veiled shout-out to Parkin’s novel in the form of Major Blake’s assertion that the Sycorax bear no resemblance to actual Martians, which actually goes some way towards bolstering my assertion that the two writers are operating from more-or-less identical principles of spectacle and iconography.

Both The Dying Days and Blake’s throwaway line rely, on some level, upon a certain proportion of the audience being the kind of Doctor Who fans who will nigh-instantaneously make the intuitive leap linking UNIT and the Ice Warriors as two groups that never got a proper on-screen confrontation, whatever the newly-regenerated Fifth Doctor might attest in Castrovalva. Indeed, The Dying Days apparently built off an abandoned proposal for a Third Doctor novel that Parkin had been toying with called Cold War, which would have featured everyone’s favourite Martians, and would have beat Mark Gatiss to the punch by about fifteen years or so, just for good measure.

Mind you, the extent to which both works lean on this kind of fannish gap-filling is vastly different. It’s effectively baked into the very premise of The Dying Days, whereas The Christmas Invasion confines it to a single throwaway line that works just as well if you only read it as a typically witty Davies aside. Nevertheless, it’s almost reassuring that the final New Adventure should contain such strong hints towards the future of the franchise, offering one last example of just how crucial these books were in shepherding Doctor Who through the 1990s.

Even the plans of Greyhaven and Xznaal for national domination pay great attention to the external, ritualistic symbolism of the relevant iconography. Staines might dismiss any notion that the intense media coverage of the Mars 97 event is simply an attempt to recapture a sense of patriotic, jingoistic British exceptionalism at the close of the twentieth century, but the fact that he’s implicated as a co-conspirator in the ill-fated Martian coup d’état naturally disinclines us to believe his assertions.

One of the very best scenes of the novel, and undoubtedly one of the most memorable, concerns Xznaal’s coronation as King of England, which Parkin seems justifiably proud of in his 2003 commentary, to the point of lightheartedly boasting that he got to the whole “crowning an otherworldly being as the King of England” thing before Grant Morrison managed to with The Invisibles.

It’s the ultimate manifestation of the ludicrous lengths to which an obsession with symbolism and ritual has driven the conspirators, trying desperately to stick to the pre-ordained programme even as it quickly descends into a farce, with Xznaal misinterpreting the use of the Anointing Spoon as an attack on his person and being unable to fit into the vestments that the ceremony requires. It’s a putrefaction of the iconography of imperialist monarchy just as deep as that afflicting the winter berry from Xznaal’s childhood remembrances, and one which similarly allows the maintenance of a deceptively lustrous and glamorous external appearance.

Even Alexander Christian, the disgraced ex-astronaut who was once considered enough of a paragon of idealised military virtue that he was chosen to fill the vacancy in the Scots Guards left by Lethbridge-Stewart’s secondment to UNIT, suffers a fate which possesses a certain symbolic horror to it.

Imprisoned on The Sea Devils‘ Fortress Island after being framed for the murder of his crewmates, he seemingly hasn’t been so much as photographed in decades, and the novel repeatedly stresses that the government have buried his case so deep that few of the younger members of the armed forces have even heard of him. In a world with no shortage of sensationalist evil – and Parkin explicitly names the Yorkshire Ripper, Myra Hindley and Rosemary West in his tableau of tabloid excess – what use would The Sun possibly have for a man like Alexander Christian?

But the final big piece of symbolic logic at work within The Dying Days is, aptly enough, the Doctor himself. Here, for the first and only time, we find ourselves presented with a New Adventure headlined by the Eighth Doctor. As a result, there’s an inherent temptation to treat this as the dawning of a brave new world, and a passing of the torch that kicks off the second form of the Wilderness Years, no longer shackled by that strange, small fellow with the umbrella and the questionable taste in pullovers.

Yet, as just about everyone under the sun has observed, it’s very difficult to treat the Eighth Doctor as an established character in his own right at this point, for the simple reason that the TV movie offers the writers so little material with which to work. It was intended as the launching point for a new series of Doctor Who on television, but it ended up making such a hash of it that it ultimately gave rise to new iterations of Doctor Who in just about every medium besides television.

Trying to read the tea leaves of the television movie and divine the shape of a theoretical McGann performance in the context of an ongoing series, then, is about as difficult a task as predicting the character arc of Michael Dorn’s Worf based on no deeper evidence than the first season of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Both characters are unmistakably present, and occasionally they’re even given stuff to do, but they’re at such a nascent stage in development that it would be ludicrously ill-advised to try and anchor a whole twenty-six episode season of television around them, let alone an eight-year, 73-book series.

Faced with this profound paucity of source material – a state of affairs which will continue to hold until at least the time of Storm Warning in January 2001 at the very earliest – Parkin effectively becomes the first to engage in what will quickly become the go-to method of characterising the Eighth Doctor, which is to play the character more as a Sandiferian, alchemical symbol of what the Doctor represents. “Generic Doctor,” in other words; store brand Doctor, if you will.

Again, I might sound like I’m being unduly harsh on Parkin and McGann, but that’s not my intention at all. Neither of them can be said to have been responsible for the rather confused status quo of the Eighth Doctor going into April 1997, and in the case of The Dying Days, the fact that Parkin makes such heavy use of symbolic logic throughout the novel means that applying that logic to the Doctor himself just about passes muster.

Indeed, even when we shortly make the transition from Virgin to the early days of BBC Books, there are plenty of writers who will make a genuine effort to lift the incarnation above the roiling tide of genericism, which a more acerbic commentator than myself might describe as the very definition of a “thankless task.” The lack of characterisation in the TV movie need not be an entirely insurmountable obstacle, but it is going to prove an obstacle, and we get our first real inklings of it here, even if The Dying Days takes a rather novel approach to the problem.

Which leads us, at long last, to talking about Benny. In the times to come, we will obviously be talking about her quite a bit, as she finally asserts full control over the narrative of the New Adventures and becomes their main protagonist of choice, give or take a Deadfall, Dead Romance or The Mary-Sue Extrusion here and there. If anything, The Dying Days can lay a much greater and more substantive claim to being the first true Bernice Summerfield novel than it can to being the first original Eighth Doctor book, even if both are technically true.

The novel is very consciously structured to ease the audience into the idea of a reformed New Adventures line to be headlined by Benny, shrewdly introducing us to the action of the novel from the perspective of her lengthy stay at the house on Allen Road awaiting the Doctor’s arrival.

This, of course, all reaches its natural conclusion in the eleventh chapter, where it appears that Parkin has chosen to kill off the Doctor, as it was rumoured he would in the lead-up to the novel’s release. Again, as many have pointed out, this is yet another instance of the book relying on knowledge of the cultural context in which it sits, going so far as to ensure the final scene revolves around the Doctor’s absence, just to trip up any overly credulous readers who might be intended to skip to the last page and find out if McGann really has been killed.

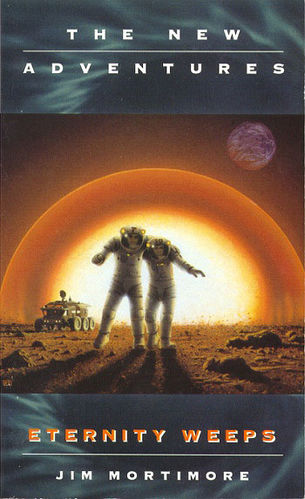

Believing that Parkin would have actually done so requires a rather far-reaching suspension of disbelief on the part of the audience – even if he had, everyone knew that there was a line of novels starring the character due to start in less than two months – but that obviously isn’t the point. No, the point is to more properly foreground Bernice, following up on the trick adopted by Eternity Weeps by treating the audience to lengthy first-person segments framed as extracts from the good Professor’s omnipresent diary.

Unlike Mortimore’s novel, these sections never completely take over the narrative, but they nevertheless exert a peculiar form of gravity on any scene in which Bernice is present, forcing the audience to reckon with her as a true protagonist in a way that we haven’t really seen her treated in Doctor Who to this point. Even the attack on Allen Road is consciously designed to parallel her actions against those of the Doctor, with both finding themselves attempting to talk their way out of a confrontation with a lone Ice Warrior at different ends of the house, before reluctantly making use of their idiosyncratic forms of ingenuity to defend themselves.

In that moment, Bernice Surprise Summerfield finally comes to wholly and undeniably embody that most classic of descriptions of the Doctor, striving to remain a woman of peace even when caught up in violent situations. Even the Doctor himself is on fine form, choosing to pause in the midst of his act of grand self-sacrifice to save a trapped cat from the wreckage of his owner’s store.

In a rather glorious bit of internal monologue from Parkin, the novel reflects on the thorough ordinariness of this kind of heroism when compared against the oftentimes planet- or universe-threatening stakes that Doctor Who can sometimes favour:

The Doctor could end wars, repel invasions, track the villain to his lair, expose master plans and wipe out evil across the universe of time and space, he could do all that before breakfast.

[…]

But if the Doctor couldn’t use his unique abilities and special powers to save the life of one little cat, then what was the point of having them?

[…]

Because when it comes down to it, doctors save lives and any life is worth saving.

It is the gradual loss of the capitalisation and definite article on “Doctor” here which is most telling, and it is this which finally clinches The Dying Days‘ status as an appropriate send-off to the Doctor as he has existed in the New Adventures, and an ushering in of the age of Bernice. There are certainly jubilant moments for the character after that point, whether it be Parkin’s frankly sublime decision to have the Doctor’s “last words” be an offer of a jelly baby to the Red Death – though a cynic might read this as yet more fuel for the fire of suspicion that we’re dealing with the realms of “generic Doctor;” on this one occasion, I am not one of these people, so I love it to bits – or his inevitable heroic return, complete with one last rousing speech about who he is, for old time’s sake.

And that’s what it all really comes down to, isn’t it? No, The Dying Days is not one of the best or most ground-breaking books Virgin ever put out. From a certain point of view, given the extraordinarily high standards that the company and its authors had proven themselves capable of achieving, some might see this as a last-minute failing, a case of ending not with a bang but with a whimper.

But such a stance fails to consider that all the bold, ground-breaking stuff was left to the sixty novels beforehand. This is the literary equivalent of a victory lap, and so in spite of the fact that McGann isn’t especially well-characterised, in spite of the fact that it’s kind of just a bog-standard alien invasion narrative that makes the bizarre attempt to only have two Ice Warriors per scene in a strangely unnecessary bit of Segal-bashing, in spite of the fact that I’d pretty comfortably consider it to be only my third-favourite New Adventure from these last four months of Virgin possessing the Doctor Who license… I can’t bring myself to dislike it at all.

Here, at this very moment, I have done something I never seriously thought I would do: I wrote reviews of all sixty-one New Adventures featuring the Doctor. Some of these pieces were leagues better than others, and when I started out I definitely didn’t take this whole reviewing thing as seriously as I did now.

There was the early embarrassing, edgy teenage overuse of swearing, that I quietly went back and corrected some time back, because frankly I just couldn’t bear it any longer and it made me wince every time I thought about it. There were the reviews that frankly got a little too mean-spirited and personal at times when I was younger, with particular apologies due to folks like Gary Russell or Christopher Bulis; I promise I’ll write less viciously-phrased reviews of Shadowmind and Legacy at some point. There were the ludicrously short and half-assed reviews, that to this day perplex me on a fundamental level.

(How did I ever think turning in a 330-word review for Apocalypse was at all acceptable? You tell me, but at least I went back and remedied that one, I suppose.)

Through it all, though, there were the New Adventures, a series that I loved and cherished through all its ups and downs. There were Adjudicators and Also People, psychic vampires on the Titanic and common or garden variety vampires in E-Space, and a million and one other things besides.

Most of all, though, I’m just thankful for all of the people I met along the way. There are really too many of you for me to ever hope to do you justice by naming you all, but the people who I’m talking about will already know. I like to think that even those who I haven’t spoken to in a donkey’s age will somehow be aware on a subconscious level, but I recognise that that’s little more than wishful thinking on my part.

When I began this project, I was a lonely teenager who had very much reached his lowest ebb. If you had told that child that he would somehow manage to review ninety-seven whole books before turning twenty-one, to say that he would have disbelieved you would quite probably be the understatement of the century. He very probably wouldn’t have even believed that he would live for another five years.

But I have, and I’m here, and I’m so grateful. So that’s what this is, really. One last chance to express my gratitude and bask in the jubilation of having achieved something that I like to think is worthwhile. Because, to be blunt, if you know what’s coming up in the next post, you’ve probably already guessed that I simply don’t feel I can be very happy that time around. I will probably be very angry and sullen, in point of fact. For now, though, let’s just sit in this feeling. Whatever comes after this moment, this is the end of the New Adventures, and I think that’s a good enough note on which to finish.

(sotto voce)

Oh… no… it… isn’t…

Miscellaneous Observations

As I also noted with Chris’ private little war on the Ice Warrior base in GodEngine, it’s rather striking, from a post-9/11 standpoint, to see a novel in a popular science-fiction franchise so cavalierly describe fan favourite characters like UNIT as partaking in tactics explicitly likened to those of terrorists. Guess there’s really just something about the Ice Warriors that brings these sorts of ideas out of Doctor Who, huh?

On the subject of the Secretary of State for Education and Science, it’s perhaps a tad ironic in light of No Future that the next-longest serving holder of the position from the 1970s was Labour’s Shirley Williams, posited by Cornell as being the unnamed female Prime Minister from Terror of the Zygons rather than Thatcher.

Despite having a ton of plot points from Doctor Who novels “spoiled” for me over the years in the course of researching them in order to feel qualified to speak on the matter, somehow the fact that Eight ends up giving Benny the Seventh Doctor’s umbrella completely slipped my attention, so it hit hard. I mean, it still would have done regardless, but on this one occasion it was nice to be genuinely and completely surprised.

Final Thoughts

Well here we are, at an ending of sorts, but it’s far from being the last page. As I gestured to, we will be covering Gareth Roberts’ The Well-Mannered War next time, so join me for that. At the same time… it’s gonna be rough, I’m not going to lie, and it will probably be the moodier, less joyous shadow to the exuberant mood I’ve tried to project throughout this review. If you wanted to skip that one, and just decide to tune in when we’re back to doing light-hearted pantomime frockery with Oh No It Isn’t!, I would absolutely understand. Thank you for reading as much of this blog as you have, however much that may be. Until whatever will pass for “next time” in your particular case, however…

Kind regards,

Special Agent Dale Cooper