We’re approaching the fringes here, people.

Covering the Decalogs was always going to mean squirreling myself into some rather strange and almost-forgotten niches within Doctor Who continuity. That is, if I’m being totally honest, part of the reason why it took me so long to even decide to cover the first two instalments, breaking the normal chronology of my reviews to jump back more than eighteen months from the gap between Lords of the Storm and Just War and talk about an anthology that, by rights, I should have covered immediately after Tragedy Day.

Indeed, nearly thirty years after the release of the first volume in the series, it seems fair to reflect at this juncture that very few Doctor Who fans are likely to remember the Decalogs as a particularly important part of the franchise’s history, even though every collection featured at least one story from a prominent member of Virgin’s established pool of writers. The only story that’s remotely likely to be remembered by those fans with a casual acquaintance with the Wilderness Years is, for obvious reasons, Steven Moffat’s Continuity Errors.

When you compare this to the status of BBC Books’ Short Trips series, which continues in spirit more than twenty-five years later, albeit under the auspices of a completely different company, in a completely different medium, it seems fair to say that there’s something of a disparity here, and that’s honestly a shame.

Not only was the series able to attract some legitimate Wilderness Years talent, and turn out quite a few solid and creative stories in the process, but it was really the first sustained attempt at providing fans with completely original adventures for past Doctors, predating the launch of the Missing Adventures by four months. It is perhaps something of an exaggeration to declare that a company like Big Finish, say, owes the entirety of its early business model to the Decalogs, but the collections certainly laid a lot of important groundwork that later series would build on, be that in the form of novels, short story collections or, yes, audio dramas.

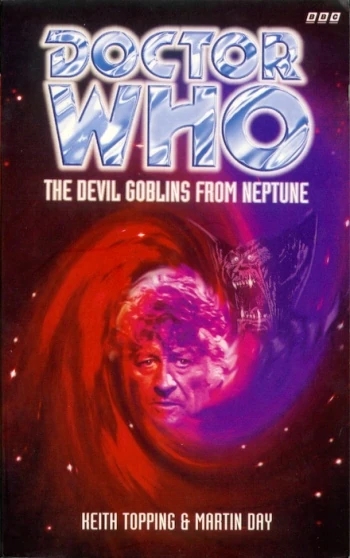

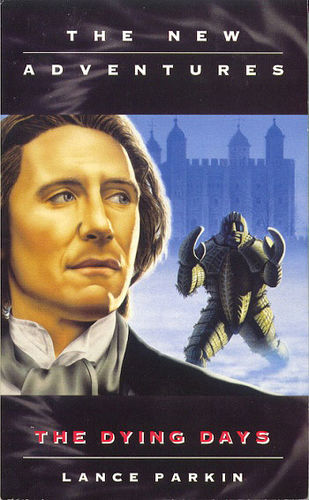

And in retrospect, one is forced to wonder whether the waning cachet of the Decalogs can be almost entirely ascribed to these final two instalments. In terms of novels, we are, of course, still in that strange and fleeting liminal space between the publication of The Dying Days – or So Vile a Sin, if you’re a particularly pedantic stickler for the release order of the novels – and The Eight Doctors, with Virgin having definitively lost their Doctor Who license at this point.

As we saw last time, the New Adventures have attempted to solve this particular problem by pivoting to cover the escapades of Bernice Summerfield, but the consequences for the franchise’s short fiction are considerably stranger. After the publication of Consequences in July 1996, the third and final Decalog to be released before the expiry of Virgin’s mandate for producing new Doctor Who stories, there would be a twenty-month gap before BBC Books’ inaugural Short Trips anthology hit shelves in March 1998, representing the longest such hiatus since the launch of the Decalogs three years ago.

By all accounts, it was also an unplanned hiatus, which is as good a summary as any of the chaos that we’re going to observe in the initial months of the BBC Books line. Preliminary reports in Doctor Who Magazine had suggested that Short Trips was to be released about six months earlier, being slated for publication alongside Paul Leonard’s Genocide and Christopher Bulis’ The Ultimate Treasure in September 1997.

(Eagle-eyed readers might perhaps notice that The Ultimate Treasure‘s release date was similarly buffeted about, eventually swapping places with Gary Russell’s Business Unusual and taking the August slot. Like I said, chaos.)

Although the interior workings of BBC Books from this time are still rather hazy, it seems likely that the collection was delayed by the company making an editorial switchover from the hands of Nuala Buffini – who found herself in the supremely unfortunate position of being arbitrarily lumped with the stewardship of the Doctor Who range despite having very little knowledge about or attachment to the franchise – to those of Stephen Cole, an impression which becomes all but inescapable once you consider Cole’s eventual status as Short Trips‘ editor, to say nothing of his three pseudonymous writing credits within the collection proper.

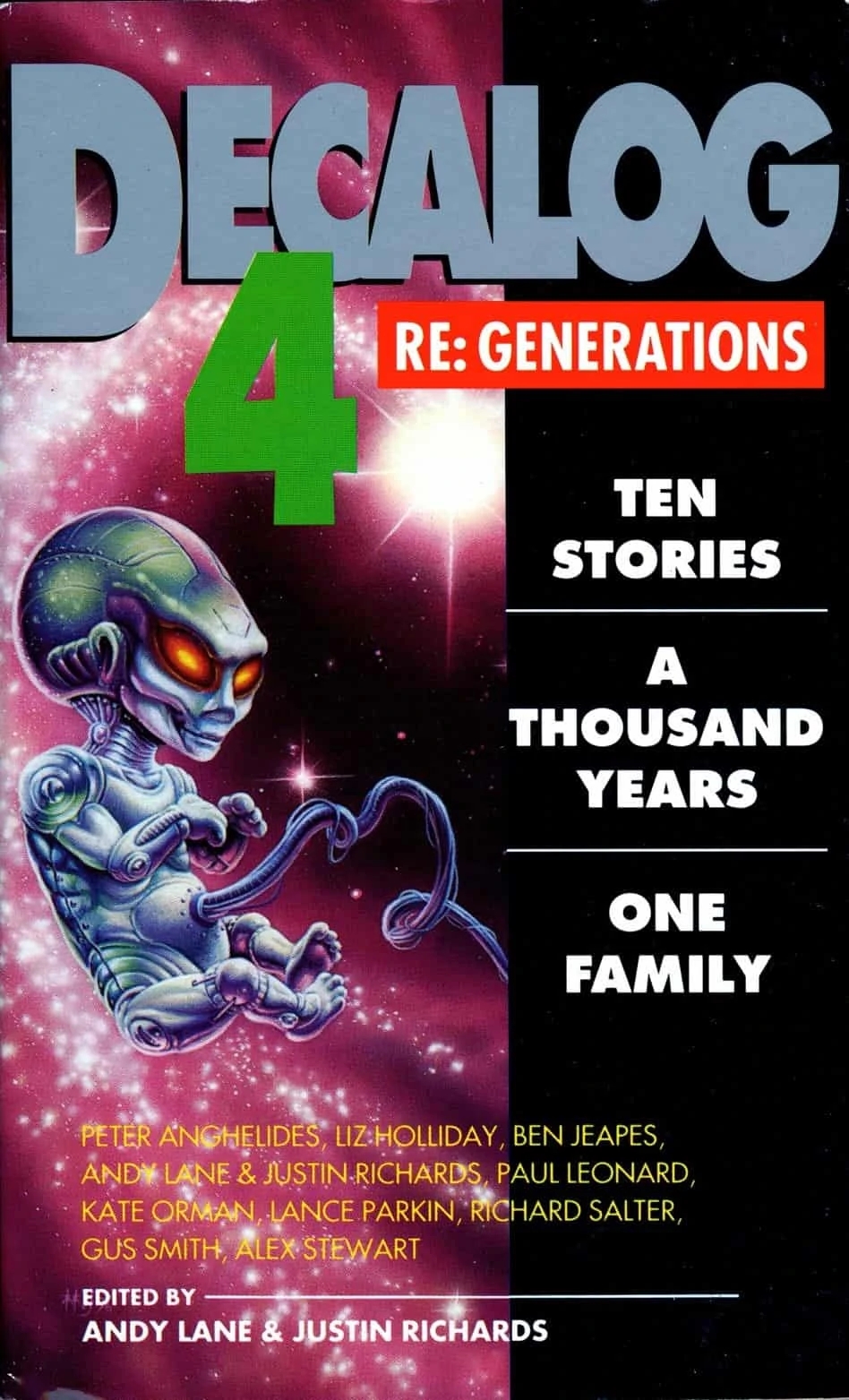

Virgin thus found themselves with an unexpected grace period, a span of time in which they were the only people putting out anything vaguely resembling Doctor Who short story collections, and Re:Generations is the first of their two attempts to capitalise on this newfound opportunity. Rather than take the more obvious route of, say, building the collection around short, sharp solo adventures for Benny, they instead opt for something a little more interesting, with each of the customary ten stories here exploring the life of a different extended family member of one Adjudicator Roslyn Forrester, across a millennium’s worth of history.

In a way, it’s a gesture that seems to serve as the final apotheosis of the increasing emphasis that the New Adventures put on charting out a credible and internally consistent “Future History” from Love and War onwards, while also making plain the degree to which the role of the companion had been rapidly expanded in the decade since Ace joined the television programme in Dragonfire.

To compare against the last time the franchise was dealing with a four-person TARDIS crew as a matter of course – as Roz’s tenure did, at least before Benny’s wedding in Happy Endings – it seems doubtful that one could have ever envisioned Nyssa, Tegan or Turlough ever being able to withstand the weight of this kind of treatment, interesting characters though they may have each been. Re:Generations is only remotely possible thanks to the work done by novels like The Also People or So Vile a Sin in giving Roz a distinct and readily comprehensible point of view on the universe around her, shaped by her own personal history.

But even with all of that being said, it does mean that we’re just about brushing up against the limits of how far I’m willing to go into the weeds of Wilderness Years literature. We’re not quite at the very edge, mind you. I’ll save that for Wonders, where there’s basically only one story that even remotely ties into the larger Doctor Who universe, and maybe two depending on how kind you’re willing to be towards Stephen Marley.

For now, though, let’s put aside just as much of that “future context” baggage as we would be willing to lose in the confusion of a particularly crowded airport terminal, as we celebrate both the sixtieth anniversary of Doctor Who and the one-hundredth book ever reviewed on Dale’s Ramblings, and I try and see if my writing style can adequately recreate… well, the confusion of a particularly crowded airport terminal, as it happens.

It’s as apt an analogy for the experience of this blog as any, I feel…

1. Second Chances by Alex Stewart

Second Chances starts us off with the sole Doctor Who contribution from writer Alex Stewart, perhaps better known these days to fans of the Warhammer 40,000 series by his pseudonym, Sandy Mitchell, a name under which he wrote the ten-book Ciaphas Cain series from 2003 to 2013, as well as two novels in the Dark Heresy series.

Taking a glance at his page on the Internet Speculative Fiction Database – where I expect I’ll be spending quite a bit of time for the reviews of both this collection and Wonders, given the branching out into writers less directly connected with Doctor Who fan culture – I’d tentatively hazard a guess and say that his most prestigious publication at the time of May 1997 would probably have been Temps, a 1991 anthology that he co-edited with none other than Neil Gaiman.

(Its central premise seems to boil down to “people with superpowers are commonplace and the government forces everyone with such powers to register and be on call to save the country,” which doesn’t sound especially original these days when we’re so inured to superheroes as a concept in the wake of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but I dunno, maybe it was great at the time. I can’t really find anyone discussing this anthology at great length, and I mostly just bring it up to note that one of the collection’s contributors, not so coincidentally, is Liz Holliday, about whom more in about four stories’ time. And also Kim Newman, who we won’t be talking about for a much longer span of time… and relative.)

There would perhaps be a temptation to try and see if there are any inklings of Warhammer-esque stylings at play here, but the fact that I am almost wholly unfamiliar with the franchise certainly does me no favours, so you’re probably looking in the wrong place for that kind of analysis. Nevertheless, it should also be noted that Second Chances seems to be playing in a cyberpunk sandbox that owes much more to the work of William Gibson than it does to Games Workshop.

Obviously, this isn’t the first time the Virgin novels have messed around with cyberpunk. Ben Aaronovitch’s perennially controversial Transit had established the genre as a foundational element of the series’ view of Earth’s Future History, although novels like Warhead and Love and War had already hinted at that particular development even earlier.

In the intervening years, however, cyberpunk had well and truly established itself as a cultural force to be reckoned with. When Jan de Bont’s Speed became a smash hit, Sony Pictures saw fit to capitalise on Keanu Reeves’ newfound status as a cinematic man of action by editing Robert Longo’s adaptation of Gibson’s 1981 short story Johnny Mnemonic into a more conventional action film. Gibson would also pop over to The X-Files less than a year after the publication of Re:Generations, contributing Kill Switch to the programme’s fifth season in February 1998 with the aid of longtime collaborator Tom Maddox, and the duo would return in the seventh season with First Person Shooter.

By the close of the decade, audiences would also be treated to David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ – featuring some English fellow by the name of Christopher Eccleston, but I have no idea who that even is so we’re just gonna breeze past him – alongside Dark City and The Matrix. That list, admittedly, does begin to show the cracks in any attempt to describe the genre as ever finding lasting mainstream success, with The Matrix really being the only credible candidate that could be said to have made a huge splash on release.

Even with most of the other films on the list having achieved some measure of cult classic status among science-fiction devotees in recent years, The Matrix seems forever destined to serve as the cultural touchstone for the 1990s interest in cyberpunk within the minds of the general public.

Still, for all that the box office returns might not have been there, the fact that so many writers and directors hit upon the same idea nigh-simultaneously is usually a pretty good sign that the concepts at hand speak to some deeper discomforts at work in society writ large, and Second Chances slots neatly into that trend.

Indeed, for all that the loss of the Doctor Who license has seemingly forced Virgin to play a bit coy in slotting the events on Pellucidar Station into a given point on humanity’s timeline as established in the New Adventures, the talk of drones and colony ships only just starting to venture beyond Pluto would seem to anchor Second Chances in the general vicinity of Transit, an impression broadly confirmed by Heritage‘s dating of the Mandela‘s departure from Earth to 2059.

And to Stewart’s credit, he provides a story that builds pretty well off that established setting, which is precisely what the first entry in a collection like this should do. As we’ve said, the Decalogs really need to prove themselves capable of pulling from the tapestry crafted by their NA forerunners, and while I doubt I’ll come away from Re:Generations thinking of this as the best story in the collection, I understand why Lane and Richards made the decision to position it as the introduction.

The central conceit is a pretty clever one, with one John Michael Forrester suddenly collapsing on the way home from his maintenance job and seemingly awakening to find himself trapped in the datanet, with everyone he attempts to contact seeming to believe him to be dead. Intrigued by this mystery, he sets out to find the individuals responsible for his death. Think Jerry Zucker’s Ghost if it was written by Raymond Chandler, essentially.

Or at least, a version of Raymond Chandler who knew what the Internet was…

The biggest problem here is something that we should be pretty familiar with, more than thirty stories into the Decalogs as we are. There simply isn’t enough time to get to know this particular Forrester, and the obvious lack of any easily recognisable TARDIS team to latch onto only exacerbates the issue.

This is a twenty-two page story, but John collapses on the sixth page, and from there we spend about nine or ten pages with his investigations before we come to the realisation that we’re actually following the escapades of an artificial intelligence that merely believes itself to be John. From there, he saves his guilt-stricken “murderer” from a suicide attempt and runs off into the sunset… or I guess doesn’t, since he’s travelling in interstellar space, but you get what I mean. We get enough context as to the type of person John is that it’s not a completely wasted exercise, yet it still feels like Stewart could have done with some more breathing room.

With that being said, I do like the way in which all the plausible motives set up in the early scenes of John’s work life are steadily demolished, with the whole thing coming down to a simple mugging gone wrong. It’s a bit ruthlessly functional, sure, and not the most unpredictable of resolutions – and the same can be said of the obvious parallel between John’s lost sister and Madge’s near loss of Cal – but I think it still has the desired effect.

In fact, it’s hard not to detect at least a faint inkling of social commentary in the setup of the mystery here. This is, at its heart, the story of a working-class Black man stuck watching the investigation into his own death from the outside, and the chief investigator proves totally unable to ascertain the truth without a tip from Eddie de Soto, a man written off as an “indigent” and a loan shark by the paycops – a phrase which, incidentally, surely serves as one of the more sinister invocations of a police-industrial complex I’ve ever heard. There’s a sense that the bulk of the paycops, institutionally speaking, embody McLusky’s solemn declaration that “[somebody] has to keep the streets clean,” and refuse to take a much more active interest in the community beyond that mandate.

It’s hard to discuss commentary of that nature within a British science-fiction context without touching upon the murder of Stephen Lawrence, an eighteen-year-old Black man murdered while waiting for a bus in Eltham on April 22, 1993. Although six suspects were arrested in connection with the crime, none were charged, and the Metropolitan Police Service came under heavy criticism from the public, including a memorable Daily Mail headline in February 1997 which accused the suspects of being murderers and directly challenged them to sue the publication for defamation.

Two months after the printing of Re:Generations, newly appointed Home Secretary Jack Straw would order an inquiry into the incident, and the findings contained within the so-called Macpherson Report found the MPS to have been incompetent and institutionally racist in their handling of Lawrence’s murder.

Second Chances never stresses the point too heavily, and most of this is just ambient background noise – though there is some neat symmetry in the story’s namechecking Tower Hamlets, which had, in the same year as Lawrence’s murder, elected Derek Beackon to become the first ever British National Party candidate to sit on a local council – but it does help lend some additional weight to what might otherwise be a humdrum bit of cyberpunk. Far from being a transcendental effort on the part of the Decalogs, but it’s certainly not a bad way to start out the collection by any means.

2. No One Goes to Halfway There by Kate Orman

Looking back, it’s honestly quite astounding just how busy Kate Orman has been throughout 1996 and 1997. The Left-Handed Hummingbird, Set Piece and SLEEPY had all been separated from each other by a little over a year, but the latter half of 1996 saw the writer step up the pace of her output considerably.

Not only that, but with the exception of the entertaining diversion that was Return of the Living Dad, most of her assignments in this period tended to be pretty weighty and consequential pieces. The Room With No Doors needed to tie up all this Time’s Champion malarkey and give something approaching a conclusion to Chris’ character arc, while So Vile a Sin required Orman to step in to perform extensive literary surgery upon Ben Aaronovitch’s ailed manuscript.

Even two months from now, Vampire Science will effectively be forced to serve as the “proper” introduction to the Eighth Doctor and Sam Jones, if only because Terrance Dicks had so horrifically botched his own attempt at that task in The Eight Doctors.

No One Goes to Halfway There, then, is an odd duck, perpetually overshadowed by the many, many genuine Orman classics surrounding it. It’s too much to seriously argue that this is some undiscovered gem on par with The Room With No Doors, because it really isn’t. It simply can’t outclass that novel in terms of raw thematic weight, nor can it even feasibly match the sprawling, epic grandeur of So Vile a Sin.

Equally, however, we ought to return to one of the oldest truisms in these Decalog reviews, namely that it’s rather unrealistic to hold short stories and novels to quite the same standards. More to the point, there’s always a certain baseline level of finesse that you can expect from an Orman story, and this one is no exception.

If the overall impression left by Second Chances was that of a broadly functional yet slightly detached exploration of an unabashedly “hard SF” concept, Orman predictably proves herself considerably more adept in her handling of similarly heady concepts. The central threat of No One Goes to Halfway There is, after all, that of an incomprehensible extradimensional being extruding itself into our paltry three-dimensional world and wreaking havoc in its wake, and there’s plenty of talk of accretion discs and black holes and all that good stuff, so if nothing else, you certainly can’t fault the story for thinking small in its science.

This being Orman, though, there’s still a recognition that the human dimension is the most important of all in a story like this. No One Goes to Halfway There is only about six pages longer than Second Chances, and yet the friendship between Theresa and Peta feels far more fully-formed than any of the myriad interpersonal relationships that John was a part of, buoyed considerably by the space afforded to smaller, low-key scenes to actually establish the emotional stakes for these two people who inevitably find themselves caught up in the throes of tragedy.

Even a character like Bob, who is only ever discussed or reminisced about by others, is still charted with enough skill that we get a pretty good sense of what he must have been like before the unfortunate run-in with the extradimensional object that sets the plot into motion, and feel some small yet tangible sense of loss at his passing.

Theresa herself is also interesting as the first Forrester in the collection to definitively live in a time where the family is possessed of considerable wealth and influence. That certainly could have been true of John, but the fact that he was stuck in a rather working-class maintenance profession would tend to suggest otherwise.

Naturally, with her status as a pariah who fled from the family fortune to take on a less prestigious role, Theresa seems destined to invite comparisons to Roz, but the tenor of the glimpses we see of her interactions with the family feels just different enough that it doesn’t feel like a bland retread.

For one, one never got the sense that Roz was having to actively avoid the investigations of her family into her whereabouts as Theresa does here, an impression which will basically be solidified by the time we get to Dependence Day. On the contrary, Leabie and co. seemed reasonably content to allow the latter-day Forrester to pursue a career in Adjudication. It’s only after her disappearance in the wake of Original Sin that the family’s feelers start to be extended throughout the Empire in earnest.

Although the Forrester family doesn’t seem quite as powerful as all that in Theresa’s time – there’s not a Baronial Palace in sight, I tell you! – they still hold enough clout to untangle their wayward daughter’s trail of bribes and obfuscations and track her down to the solace of the Triton pilot school at which she’s taken up residence, rendering them a decidedly sinister force in a way that can’t help but shake some of the audience’s perceptions about the family whose rise we’re charting throughout this collection.

We also get to witness Orman at her most gleefully experimental in her willingness to actively toy with the form and construction of her stories, which has been a recurring feature of her work ever since the phenomenal “stopping the tape” sequence back in the days of The Left-Handed Hummingbird.

Here, there’s a sense that she’s really pulled out all the stops. The story bookends itself with diary entries from Theresa, the first of which starts out in media res before jumping back three weeks. The space flight sequences are delivered in the form of a chat log, while the footage from Bob’s visual log becomes a shooting script. It’s even structured so as to have two cleanly delineated “parts,” and the numerous section titles peppered throughout start indirectly commenting upon the dialogue of the characters at certain points.

Some of this might run the risk of falling under the category of “trying to be too clever,” but Orman has a strong enough grasp of her abilities at this stage that she’s able to make it flow pretty smoothly, and there’s nothing here that manages to be as awkward as the bullet-pointed Ant attack on the Parisian chateau in Set Piece.

(I’ll take “Sentences That You’d Only Hear In Relation To Doctor Who” for $500, thank you very much…)

Another point which one might instinctively balk at is the lack of a precise explanation as to the nature of the probe attacking the colony on Halfway There, but that’s only really a problem if you have an absolute zero-tolerance policy towards any sort of intentional ambiguity in your fiction. Indeed, it would perhaps be more accurate to say that we are provided with multiple competing answers to the question, which is in many ways the more interesting option anyway.

If you were to force me to put my money where my mouth is and give my opinion as to the “correct” explanation, I would probably say that I side with the notion of it being some kind of incomprehensible alien artist. Even aside from its twisting every object it comes into contact with into strange and abstract shapes, there seems to be the suggestion that its presence induces some measure of violence upon the very fabric of the story in which it’s housed.

Theresa notes that, besides Peta, the bedraggled survivors of Halfway There with whom she falls in seem to have had their personhood erased in some fashion. The collapsing debris from the colony’s central complex is said to fall into a “discontinuity,” a rather choice selection of wording that should make the ears of any self-respecting modern science-fiction fan prick up.

But perhaps the most revealing change wrought by the strange being seems to be an alteration of the characters’ ability to utter profanities, with the radio logs’ judicious use of “[expletive deleted]” giving way to no less than two uses of the word “fuck” in the back half of the story. For Virgin, this shift carries a deep symbolism, given how seismic the initial controversy over Transit‘s whole-hearted embrace of cursing and sexuality was.

There’s certainly something delightfully cheeky in the decision to so readily return to the reckless abandon with which those early NAs treated the topic, but it also serves, in a roundabout way, to reaffirm Re:Generations‘ status as a fringe bystander on the very edge of the Wilderness Years fracas.

After all, Virgin only really gets to enjoy this kind of freedom by dint of their no longer having to serve as the public face of new Doctor Who, and there’s a sense in which BBC Books’ reclamation of the franchise’s prose license has visited an incomprehensible artistic violence all of its own upon the identity of the NAs and Decalogs. They can act out and use all sorts of foul language, but the simple fact of the matter is that nobody is liable to take much notice anymore.

After nearly six years, no one goes to the New Adventures.

3. Shopping for Eternity by Gus Smith

Given Gus Smith’s status as a one-time contributor to the world of Doctor Who, I was initially hoping to give him the same treatment as Alex Stewart. Unfortunately, his entry on the ISFDB is stunningly bare, with Shopping for Eternity being one of a mere six short story credits that he has to his name, alongside a full-length dark fantasy novel from 2001 set in Newcastle entitled Feather and Bone, whose Goodreads blurb promises an exploration of “child abuse, poverty, homosexuality, retirement, and paparazzi.”

Oh and also, one of the aforementioned six short stories bears the glorious title of The Incorporeal Crapshooters from the Ghost Planet Kring. That’s all I have to say about that, really. Other than, y’know, I’d really like to read it.

So, with all of that out of the way, I guess we really have no choice but to talk about Shopping for Eternity. Thankfully, that’s no great loss, as this was probably my favourite story thus far, and a pretty solid contender for one of my favourites across the entirety of the Decalog series.

Admittedly, if you strip it back to the basics of its plotting, it doesn’t exactly seem like it’s up to much. It’s a pretty simple story about another Forrester – Jon, this time, a name which is unfortunately close to John from Second Chances, and which is the type of mildly confusing thing you’d have hoped Lane and Richards might have caught somewhere along the line – finding himself embroiled in a web of corporate intrigue, with the slightest tinge of a religious-inflected space Western about the whole thing.

Somewhere along the line, however, Shopping for Eternity manages to become far more than the sum of its parts, and offers up a bitingly cynical exploration of 1990s corporate America, the rise of the religious right, and the media manipulation that bridges the gap between the two.

Particularly attentive readers will, in all likelihood, recall that we’ve made quite a big deal of late about the degree to which we are presently situated in the superficial peak of the so-called Third Way, with Tony Blair’s newly-elected Labour government still having spent only two weeks basking in the golden afterglow of their landslide victory, bringing to a close eighteen consecutive years of Conservative Party dominance. Clinton, too, is pretty comfortably positioned to ride out his second term, provided we don’t end up with a particularly sordid Oval Office sex scandal on our hands.

But this narrative is, by necessity, incomplete. Obviously, one can’t talk about the character of the strange unipolar moment that was the 1990s without eventually gravitating towards figures like Clinton and Blair, and they certainly make up a substantive portion of the era’s history, yet if you want to talk about the long-term impact of the decade upon the global political culture, you also simply can’t avoid talking about the religious right.

Like any good nebulously-defined sociopolitical trend, it should be stressed that the religious right didn’t spontaneously pop into existence one not-so-fine day in the mid-1990s. Rather, the decade’s more visible manifestations served as a boiling over of pre-existing tensions. Most commonly, this is dated to the mid-1970s, and to Gerald Ford’s pursuit of the Catholic vote in the wake of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, although there are certainly shades of religiosity to be found in the Southern strategy employed by Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon in the 1960s.

Still, there had been a pronounced skewing towards Christian voters at play within the Republican Party, a trend which only grew more evident throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s. Southern Baptist minister Pat Robertson of the Christian Broadcasting Network served on a number of task forces and committees throughout the Reagan presidency, and although the preacher would lose his bid for the Republican presidential nomination to Vice President George H. W. Bush in 1988, his campaign is generally credited with being a watershed moment in the religious right’s realisation that they could feasibly mobilise themselves given enough media savvy and know-how.

Untangling the facets of the conservative media machine that sprung up in Robertson’s wake could undoubtedly fill thousands of words in its own right, but suffice it to say that it is this ability to weaponise a rapidly-evolving media landscape which arguably proved the most insidious legacy of 1990s conservatism. For vindication of this, one need only look at how many pillars of the modern right-wing misinformation machine got their starts in the decade.

Rush Limbaugh may have achieved national syndication in 1988, but he hit The New York Times Best Seller List with the publication of his first two books in 1992 and 1993. Fox News started broadcasting to an audience of seventeen million cable-viewers in October 1996, while the Drudge Report – soon to be pivotal in the breaking of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal, and hiring one Andrew Breitbart for good measure – had begun its life as an email-based gossip column a year earlier. Alex Jones’ InfoWars would eventually go online in March 1999.

All of this, as you might have surmised by now, leans rather heavily on an American perspective of the 1990s, rather than the more obvious British lens which more frequently presents itself when talking about Doctor Who, but in fairness much the same is true of Shopping for Eternity itself.

It’s pretty clear that Smith has drawn from a religious iconography more specific to the United States in his crafting of New Zion. The very name of the planet evokes the Christian Zionist eschatology that was gathering steam among evangelicals at the time, while Jon’s ill-fated son et lumière performance at the theatre in Rehoboth seems consciously modelled upon televangelist megachurches in the grand Joel Osteen tradition. Osteen-tation, if you will. The people of Ebenezer, on the other hand, recall distinctly American religious subcultures like the Amish and the Mormons, or even more contemporary and straightforwardly cultish examples like David Koresh’s Branch Davidians.

Through all of this, the twin spectres of the Pabulum Corporation and its attendant consumerism haunt our wayward Forrester at every turn, and it’s definitely quite compelling to watch. Much like the eschatological and religious fears running through Shopping for Eternity, there’s a sense that Pabulum is grounded firmly in the 1990s.

We’re told by the trusty Tranlis Difarallio that the story unfolds in the wake of the conflict between humanity and the Daleks – sorry, “ruthless, implacable alien foes”- with the corporations spreading their influence throughout the resulting power vacuums that sprung up across the disadvantaged and forgotten colonies at the fringes of human space. It is, in short, a pretty close match for the kind of economic globalisation that went into full swing in the final years of the twentieth century, insofar as terms like “global” can really apply to interstellar distances.

Even the corporation’s methodology seems to owe more to a sort of sinister capitalist logic than it does to open belligerence, as we’re informed that the company typically likes to allow particularly pioneering individuals to do the hard work of settling and terraforming a new world, only to swoop in and reap the long-term benefits of that labour. The scale of their Machiavellian manipulations here runs the risk of seeming contrived, turning every part of New Zion society encountered by Jon into a means of entrapping him into the role of unwitting Messiah, but it’s a testament to Smith that he absolutely sells the operatic tone of the piece to the point where I, at least, completely bought it.

Indeed, if this story were released a few years later, one might almost suspect Pabulum of being a thinly-veiled commentary on the kinds of megacorporations that were increasingly coming to dominate life in the Western world, but since we’re still in the earliest days of companies like Amazon, and we haven’t even so much as seen the foundation of other major players like Google or Netflix, that seems like a bit of a stretch.

The closest parallel you could probably draw would be to Microsoft, whose bundling of Internet Explorer with Windows 95 was coming under increasing scrutiny, culminating in a motion from the Justice Department ordering the cessation of the practice in October 1997, and eventually to the company’s being labelled an “abusive monopoly” in United States v. Microsoft Corp. in 2001.

Still, all of this just speaks to how well Shopping for Eternity has aged in the intervening quarter of a century. Not only that, but there’s a charming satirical edge to many of Jon Forrester’s interactions, which helps the story breeze by, ratcheting along to a showstopping conclusion in the most literal of senses. Plus, it features an all-too-tantalisingly brief appearance by The Incorporeal Crapshooters from the Ghost Planet Kring.

That alone makes it worthy of commendation.

4. Heritage by Ben Jeapes

Heritage marks the second occasion on which we’ve run into Ben Jeapes, following Timevault in the previous collection. It’s also the last such occasion, as he never again contributes to Doctor Who past this point.

Broadly speaking, Timevault was a perfectly serviceable little story which was dealt an astronomically bad hand by being positioned right after Steven Moffat’s legitimately brilliant Continuity Errors. Personally, I found its biggest fault to be the inability to adequately commit to either of its two big ideas, starting out as a pandemic thriller with a race against the viral clock, before suddenly and inelegantly throwing in the return of a long-dead species out to get vengeance upon the Time Lords.

Still, having too many ideas is at least a novel problem for a Decalog story to be plagued with, and Jeapes had a solid enough grasp on the characterisation of the Doctor and K-9 that I still found myself interested in seeing how his sophomore effort would shape up. Having just finished Heritage, however, I find myself more conflicted and confused than ever.

On the one hand, yes, Jeapes has wisely pulled back the scope of his ambitions so that the premise can be adequately and succinctly summarised with a minimum of hassle and without sounding like two completely separate premises disjunctively glued together. What’s more, the premise is actually one of the more creative applications of the collection’s core structure, centring on the discovery of John Michael Forrester’s long-lost sister Billy on board the sleeper ship Mandela some three-hundred years after the events of Second Chances.

Intellectually speaking, all the pieces are there for a story that I might really enjoy. The stage is set for some kind of exploration of the mutable and shifting nature of family history, perhaps personified by the twisting of the Forresters’ origins in the Nelson Mandela housing estate in Tower Hamlets into a direct familial connection to the man himself. By rights, we should be looking at another grand, operatic tragedy, but for whatever reason, it never quite materialises.

One of the biggest hurdles doesn’t even come from the text of the story itself, but instead from the standard Difarallio prelude that sets the scene. Jeapes has very clearly structured Heritage so as to preserve the twist of Chandos’ not actually being a member of Earth’s official naval forces.

In fact, for the particularly genre fiction-obsessed members of the audience, the deception is carried a step further, with the basic idea of a “modern” starship’s crew awakening a group of cryogenically-frozen colonists from centuries in the past bearing a striking resemblance to the first season finale of Star Trek: The Next Generation, The Neutral Zone. Actually, to be fair, I was gonna let Jeapes off the hook a little here and not even mention it, but he did rather force my hand by explicitly identifying the present year as 2364, i.e. the exact same year given by Data in the corresponding TNG episode.

(In a similar vein, New Canaan is so consistently referred to as a “Codominium” that I can only assume it isn’t a misspelling of “Condominium,” but rather a conscious nod to Jerry Pournelle’s CoDominium series of novels. I mean, it could just be a misspelling, but I do like to give writers the benefit of the doubt and presume some level of intentionality behind everything they put in their works.)

As the story wears on, however, what initially seems like another in a long line of uninspired Star Trek homages in 1990s Doctor Who becomes something far shrewder, utilising the audience’s own potential familiarity with what the story initially appears to be in order to deceive them into believing Chandos to be a different sort of character than he is.

Or at least, that’s the theory. For some unfathomable reason, though, Lane and Richards – who I’m assuming are the writers of the Difarallio paragraphs – saw fit, in listing the kinds of occupations held by the Forresters in this brave new world of the 2360s, to float the possibility of members of the family serving as “opportunistic raiders and pirates.” As such, the degree to which the revelation that Chandos is, in fact, an opportunistic raider and a pirate can actually be considered a “surprise” is severely compromised from the jump.

Then again, I’ve never really been one to nitpick or complain about twists being “spoiled,” and I’ll admit that I’m being atypically granular in my reasoning here. In fact, I’d probably be willing to write it all off as a minor hiccup if Chandos actually made for a remotely interesting villain, but, as you might have guessed, he doesn’t. “Why?” Billy implores her wayward descendant after he enacts a particularly cold-blooded bit of murder towards the story’s climax. “Because,” is his eloquent and well-considered response.

Truly Shakespearean, I tell you.

It’s not that all your villains necessarily have to have especially fleshed-out or fully-formed reasons for their despicable acts, nor do you even have to make them overtly sympathetic, but if you’re going to try and sell me on the ostensible “tragedy” of their fate, then it probably couldn’t hurt. At the very least, you’re going to need to give me some reason to care about someone who’s willing to wipe out an entire colony and a sleeper ship to preserve their piracy racket, or else the sum total of my emotional engagement with the story will probably be a non-committal “Eh, serves him right.”

That’s the problem at the heart of Heritage, really. It wants to be grand and epic and soaring, but for all its basic competence at telling a story – and, unlike Timevault, at understanding which stories it wants to tell to begin with – it never quite manages to land its punches.

(Also, the casual inclusion of an attempted rape of Billy is already a cynical enough ploy to hit the audience’s “Ooh this is edgy and uncomfortable” buttons as is, but it’s made infinitely worse by the decision to have Chandos rescue her and, by extension, preserve his image as a “good guy” in the audience’s view a little longer. It’s a rather crass, careless and narratively utilitarian handling of such a delicate issue, but then that’s Heritage in a nutshell, isn’t it?)

5. Burning Bright by Liz Holliday

Liz Holliday presents us with yet another one-and-done writer to mull over in regards to Re:Generations, although thankfully the arc of her general career is easier to quantify than that of someone like Gus Smith. A quick consultation of the ISFDB, alongside skimming an archived About the Author blurb from an old science-fiction magazine from 2007 – which I definitely didn’t find by employing such gauchely prosaic methods as looking at the Reference list for Holliday’s page on Wikipedia, mind you – reveals her to have been a pretty prolific contributor to the worlds of British speculative fiction, eventually serving as editor for such science fiction publications as Odyssey and Ben Jeapes’ own 3SF.

(I’m assuming the former is completely unrelated to a similarly-named South African magazine devoted to holistic and New Age ways of living, but at this point I’m not ruling anything out, alright?)

Also, she was apparently featured in the Guinness Book of World Records for having held a marathon 84-hour session of Dungeons & Dragons, which is, I would wager, something that very few other Doctor Who-adjacent writers can honestly say.

In terms of her being afforded the chance by Virgin to contribute to this collection, however, the most obvious intersection with the company’s past output is definitely her contribution of three novelisations of episodes from Jimmy McGovern’s hit crime drama series Cracker – and again, that Christopher Eccleston guy pops up, will he ever go away? – being one of only two authors to have adapted a script from all three seasons of the programme; the other, if you’re keeping score at home, is Jim Mortimore.

Certainly there are visible strains of Holliday’s time spent among the weeds of crime drama television to be found in Burning Bright, although the more blatantly procedural elements are mostly confined to the very beginning, before the bottom drops out from under that style of storytelling and Impsec, a nascent form of the Adjudicators who obviously occupy a pretty important place in any history of the Forresters thanks to Roz, is revealed to be a thoroughly corrupt institution beholden to corporate interests.

This shouldn’t exactly be surprising to anyone who has paid attention to the Adjudicators as they’ve been built up throughout the New Adventures, including in Roz’s own introductory novel, Original Sin, nor is it a great break from the organisation’s obvious textual forerunners, namely the Judges from Judge Dredd. Hell, if we take Second Chances into account, this isn’t even the first time issues of police corruption have formed the thematic backbone of a story in Re:Generations. But there’s a slight shift in focus here which proves revealing, as Burning Bright chooses to introduce us to the brutality of Impsec in the context of a heated riot.

Of course, this isn’t necessarily a framing which necessitates we discard our earlier discussion of race relations in the United Kingdom entirely. Certainly, you don’t end up with a country with such stark racial divisions without riots cropping up, and the 1990s saw these tensions repeatedly come to a head. In October 1993, thousands of demonstrators gathered on Winn’s Common to protest against the BNP’s opening up a headquarters in a bookshop in South East London, and the escalating violence – spurred on by the police’s liberal use of truncheons and horseback charges – ultimately left 74 people injured.

In the aftermath, Stephen Lawrence’s friend Duwayne Brooks, who had been with him at the time of his death, was among those charged by the Metropolitan Police for their involvement in the riots, although it later emerged that these charges were part of an attempt by the Special Demonstration Squad to discredit the organisers of the campaign demanding justice for Lawrence’s murder. The charges would later be dropped, and Brooks was awarded £100,000 compensation in 2006. Similar riots broke out in Brixton and Bradford in 1995, the latter of which has largely been overshadowed in subsequent years by the more extensive rioting witnessed by the city in 2001.

Still, there’s something to the heavy focus Burning Bright affords the role of media coverage in the inflammation of these tensions which can’t help but bring to mind the Los Angeles riots of 1992, and the lingering after-effects that would be felt in the years to come, perhaps most infamously in the media circus that the O. J. Simpson trial wound up becoming… which I actually talked about when discussing Guy Clapperton’s Tarnished Image last time, so, hooray for the rhyming of history, I guess.

Holliday seems to demonstrate a certain canny awareness of the way news coverage can significantly slant public opinion, and while it would be frankly laughable to suggest that the country which serves as one of the staunchest bastions of the Murdoch press doesn’t have its issues with horribly skewed reporting, the frenzy that gripped reporters in 1990s Los Angeles still seemed to operate on a whole other level. After all, it’s hard not to read the introduction of Kenzie, attempting to record the violent excesses of Impsec, without being put in mind of the infamous videotape of Rodney King’s brutal beating at the hands of the Los Angeles Police Department.

(Appropriately enough, a scan of my past writing reveals that the two previous occasions on which I’ve referenced King’s case were in my reviews of Tarnished Image and Original Sin, which goes a long way towards making my point, I feel…)

If there’s one big flaw to Burning Bright, it’s that these ideas of police brutality are quickly mixed with a whole bunch of unrelated 1990s concerns, which certainly makes for a thematically dense read, but prevents Holliday from ever making too substantive a statement on any one topic. Moreover, even the very presentation of the story’s ideas feels cobbled together from some kind of “New Adventures/Decalogs Greatest Hits” compilation, even to the point of reiterating ideas from elsewhere within this very same collection.

We’ve touched on the basic fears of police corruption and brutality that motivated Second Chances, but we’ve also got a bit of the Christian eschatology from Shopping for Eternity mixed in, alongside the basic premise of “There’s something weird going on with the colony’s communications satellite(s)” that we saw in No One Goes to Halfway There. Plus, after Damaged Goods, you do rather get the feeling that Virgin would have been well-advised to stay away from “drugs that mess with people’s latent psychic powers,” since it’s highly unlikely that anyone can offer a better spin on that topic than Russell T. Davies. Predictably, nobody did.

Nevertheless, this isn’t a bad story by any means, and it certainly doesn’t approach the kind of mediocrity we just witnessed in Heritage. Despite handily being the collection’s longest story, at a whopping thirty-seven pages, Holliday is shrewd enough to keep the plot moving at a steady pace. Similarly, while I’m not quite sold on Anjak and Kenzie’s relationship as being the deepest romance in the universe, the development of their grudging admiration for one another is charming enough that the ending does pack the appropriate punch, even if “And then this member of the Forrester family died horribly” is becoming something of a predictable beat for the collection at this point.

So yeah, I think the final judgment on Burning Bright is “interesting but imperfect,” and I’ve certainly read far worse stories over the course of the Decalogs. I do wish Holliday had gotten the chance to write more stories, but as is I suppose we’ll just have to chalk her up as another in the long line of writers to slip through the Decalogs’ cracks, unfortunately.

6. C9H13NO3 by Peter Anghelides

Alright, let’s get one thing straight right off the bat. There’s no way in hell I’m going to type out that title every single time I want to refer back to the story, so instead we’re going to simplify things considerably and just call it Adrenaline, which the original title basically translates to anyway. If you’ve got a problem, write to your Senator about it.

Moving along to consider the author themselves, we’re back on reasonably solid ground for perhaps only the second time since No One Goes to Halfway There, with Peter Anghelides representing the rare instance of a writer who made their debut in the Decalogs before going on to become a decently prolific member of the Wilderness Years stable in the novel lines proper.

Ultimately, the number of examples I can think of that fit that pattern is vanishingly small, particularly when placed against the overwhelming number of writers who quietly slipped out of sight after contributing one or two stories. Mike Tucker and Robert Perry would go on to serve as BBC Books’ go-to guys for contributing Seventh Doctor stories that actively pushed against all that New Adventures stuff that had proved so controversial, but Tucker had already been associated with the television programme as a visual effects assistant in the McCoy years, so it feels like a bit of a cheat to list him here.

Ditto Colin Brake, whose debut full-length novel, Escape Velocity, came nearly five years after the publication of Aliens and Predators. So really, that just leaves you with… Matthew Jones, I guess, and he’s only two months away from releasing his second and final New Adventure, and just a year out from finding far greater success as script editor of Queer as Folk.

(NB: Steven Moffat is Steven Moffat, and should always be placed in his own category.)

Of course, it seems unlikely that most people will rate Anghelides as one of the true literary titans of the Doctor Who canon when all is said and done. If we cast our gaze further ahead, we’ll find that while Frontier Worlds might land in the top thirty Eighth Doctor Adventures in the almighty Sullivan rankings, Kursaal and The Ancestor Cell both hover around the general vicinity of fiftieth to sixtieth place, with the former being a rather unassuming and traditionalist little werewolf story that’s perhaps undone by the sense in which it jars terribly with Alien Bodies, and the latter… well, the latter actually manages to jar terribly with Alien Bodies in a completely different way, so chalk one up for innovation, I guess.

(To be fair, the presence of a co-writing credit for outgoing editor Stephen Cole – the man who got the EDAs into the whole “War in Heaven” mess to begin with – at least hints that we might want to spare Anghelides somewhat in our apportioning of the blame.)

None of that can really shape my opinion too much for the purposes of this review, however, since the only Anghelides story I’ve covered so far was his contribution to the previous Decalog, Moving On. Although seemingly controversial among certain sections of fandom on its initial release, the passage of time worked in its favour, allowing it to stand as a pretty moving pseudo-epilogue for the adventures of Sarah Jane Smith and K-9, while fitting surprisingly well with the new lease on life afforded the duo in their post-School Reunion phase.

Suffice it to say, then, that Adrenaline was probably the only story in the collection that I had particularly high expectations for to start with, if one discounts those authors whom I was already familiar with from their novel-length works. That’s a pretty big qualifier, but I think it communicates the general point.

Thankfully, Anghelides ends up surpassing those expectations and then some, delivering a story which I might even like a little bit better than Moving On. It’s certainly one of the standouts of Re:Generations, and is in close competition with Shopping for Eternity for the title of my favourite story in the collection.

On the surface, one might expect me to take Adrenaline to task for the same things I lambasted Heritage for. Once again, Tranlis Difarallio drops some rather crucial information that initially seems to heavily spoil the surprise of the way in which the Forresters are involved, referring to one “John Forrester” as a crucial figure long before anyone in the story even mentions his name.

Indeed, since all the other characters refer to the story’s protagonist as “Samuels,” one assumes that Anghelides has set up a blindingly obvious mystery in which Samuels will actually be revealed to be John Forrester, buoyed by the cynical conceit of adopting a second-person narrative voice – a rarity in Doctor Who fiction to this point – and that Lane and Richards have once again gotten too far ahead of themselves and slipped in spoilers which they shouldn’t have.

Where Heritage built to an underwhelming twist and promptly found itself with no idea of what to do with Chandos beyond turning him into a generic villain wearing the blackest of hats, though, Adrenaline actually manages to weaponise the audience’s presumed foreknowledge against them, with pretty stunning results.

By the time Samuels and Bocx have broken into the Forrester Industries facility, with the former arriving at a convenient computer terminal, the stage seems set for a bog-standard reveal that our protagonist has actually been the villain the whole time. And, fair play, they pretty much do, as “Samuels” looks at a photo that matches his appearance, captioned “John Forrester.” Cue the closing credits sting… or don’t, I’m not sure if we can clear the copyright under these circumstances.

Questions start going off in your mind, however, once Bocx proclaims his desire to find and kill Forrester. After all, if he was so hell bent on revenge, you’d think that he’d recognise the guy. Deviously enough, it turns out that we’ve not only been reading the adventures of a synthetic facsimile of Forrester who’s been deliberately filled with Samuels’ memories by Bocx, but that these adventures have been vicariously experienced by the real Forrester, rendered bedridden by the same chemical fire started by Bocx, in an effort to enable his body to experience the exhilaration of the adventure’s associated adrenaline.

There’s perhaps an argument to be made that Anghelides is simply wrapping up two of the oldest and most cliché twist endings in a flashy and moderately experimental package, but there are a few reasons why this critique doesn’t really land with me personally. For starters, Adrenaline is shrewd enough to always give the audience just enough information that they can start attempting to put all the pieces together, while dangling the most crucial pieces just out of reach to prevent the game from being given away too early.

This might sound like I’m accusing the story of being nothing more than a crass and dishonest shell game, but nothing could be further from the truth. As any 1990s Star Trek writer would quite readily tell you, it’s actually supremely difficult to construct a gripping mystery in a science-fiction setting that feels like it’s “playing fair” with the audience, unbeholden as such worlds are to the laws of conventional physics, so the fact that Adrenaline just about manages it is certainly no small feat.

More broadly, though, Adrenaline is a story fundamentally concerned with the commodification and commercialisation of human beings, particularly within the bounds of the prison system. Of course, as with the exploration of racial tensions elsewhere in Re:Generations, there’s a much deeper resonance to these fears when applied to a Black protagonist like John Forrester, because… well, that kind of commodification is all too real, historically speaking.

The enshrinement of slavery as a foundational element of the United States naturally provides the most salient example here, but it’s hardly controversial to observe that the legacy of that heinous institution remains alive and well in the nation’s penal system, what with the Thirteenth Amendment being the way it is.

(I mean, if that is a controversial statement for you, then you’re probably on the wrong blog…)

The popular culture of the mid-1990s seemed particularly fascinated by issues of the prison system, especially with regards to death row inmates. Chris Carter wrote and directed The List for the third season of The X-Files in October 1995, telling a tale of supernatural revenge amidst a Floridian death row prison pretty obviously inspired by the Louisiana State Penitentiary, colloquially known as “Angola.”

Stephen King serialised his hit novel The Green Mile over six months in 1996, with the book eventually receiving a successful 1999 film adaptation starring Michael Clarke Duncan and Tom Hanks. That same year, Susan Sarandon won Best Actress at the Academy Awards in March for her performance in Tim Robbins’ Dead Man Walking, while October saw the release of The Chamber, effectively becoming the Johnny Mnemonic of this particular trend by debuting to an underwhelming-at-best critical and commercial response.

Admittedly, there’s never any mention made in Adrenaline of the possibility of capital punishment, and the impression given is that the horrors of the Callisto Penitentiary “only” really extend to unethical human experimentation, but even this has enough in the way of a real-world historical grounding that I feel comfortable identifying the story as a part of this broader literature.

We already kind of touched upon the American government’s flagrant abuses of medical ethics in the general sense last time when discussing Timevault, and a full accounting of the many instances in which these abuses have occurred in prison environments would probably be too depressing and lengthy a task to dive into here, but it’s worth noting in passing that Adrenaline saw print just one year before Allen M. Hornblum’s Acres of Skin, detailing the experiments conducted over a period of more than twenty years by dermatologist Albert Kligman at Pennsylvania’s Holmesburg Prison. The title of that book, incidentally, comes from Kligman’s reaction to seeing the Holmesburg inmates for the first time:

All I saw before me were acres of skin… It was like a farmer seeing a fertile field for the first time.

So, y’know. Plenty of commodification there, I think.

It’s also worth noting that a lot of this ties heavily into the general soul-searching mood of 1990s American popular culture, and especially the ongoing recontextualisation of the Second World War. The kind of experimentation evoked by both Adrenaline and Acres of Skin strikes uncomfortably close to that more traditionally associated with infamous Nazi physicians like Joseph Mengele, slotting neatly alongside the recurring preoccupation that many of the New Adventures of the first half of 1996 exhibited with the legacy of Nazism and the Holocaust, just in time for the fiftieth anniversary of the Second World War’s ending.

Even the reveal that the faux-Samuels’ memories have been repeated and watered down to an adrenaline factory for the withered husk that once was John Forrester plays into this sense of capitalist monstrosity, a strikingly literal form of commercialisation that affects the very narrative voice of the short story itself.

Adrenaline is another success, both for Peter Anghelides and for the increasingly impressive Re:Generations. It’s timely, clever, and possessed of an uncommon viscerality and immediacy by virtue of its second-person narration. The only real downside I can think of is that, between John Michael Forrester in Second Chances and Jon Forrester in Shopping for Eternity, greater editorial care might have been taken to avoid such puzzling nominal recurrence as happens here with our third John of the collection.

It might be realistic for a family tree spanning a good few centuries to have a few members with the same name, but it doesn’t make it any easier to write about. Still, that’s such a minor thing, and not really even the fault of Anghelides’ story at all, so I think we’ll let him off the hook.

7. Approximate Time of Death by Richard Salter

Richard Salter is the last of the four first-time Doctor Who authors to grace the pages of Re:Generations. Indeed, as far as I can tell from a brief perusal of the Internet, Approximate Time of Death seems to be his first substantial writing credit of any kind.

Unlike Stewart, Smith and Holliday, however, Salter would actually go on to be reasonably prolific in the world of Doctor Who-related short stories, becoming a frequent contributor to the Short Trips series under Big Finish’s stewardship of the title, to the point of eventually editing the Transmissions anthology in 2008, and even penning a story for the Bernice Summerfield range for good measure.

All of these stories are, of course, beyond the purview of what I’m intending to cover as a part of Dale’s Ramblings, so Approximate Time of Death represents my one and only chance to form an impression of Richard Salter. In virtually all respects, this is profoundly unfortunate, since it’s pretty handily the collection’s weakest instalment by some considerable distance.

If Heritage could at least lay claim to an interesting premise that was squandered by some poor choices on the part of Ben Jeapes, Approximate Time of Death starts much as it means to go on, setting itself up as a pretty standard-issue murder mystery involving the death of prominent industrialist Mark Forrester.

To be entirely fair, Salter manages to create some small degree of interest by injecting the added quirk of Forrester’s bodyguard managing to “predict” his death ahead of time, but any momentum which this affords the narrative is well and truly spent once the story spends eighteen of its thirty pages to actually get to the murder in question.

Even this would be forgivable if the buildup to the murder was especially interesting. In actual fact, what we’re treated to is mostly just eighteen pages of ruthless, brutal exposition in an effort to set up all the moving pieces and get to the twist in the tale as soon as possible, with character development that can most charitably be described as functional.

It’s clunky and inelegant in a way that even Heritage largely managed to avoid being, and the only mystery I was particularly invested in was my own internal quest to figure out why the name of the lead Adjudicator handling the case, Rachel Carson, sounded so familiar, before I realised that Salter seems to have simply named the character after the author of the seminal environmentalist text, Silent Spring, for no easily discernible reason. So that’s something, I guess.

(Then again, if David A. McIntee can name all the Adjudicators in The Dark Path after semi-famous British stunt performers, I suppose anything’s fair game…)

All of which brings us to the eventual twist, which is that Forrester has actually been dead for quite some time, with all the scenes narrated from his point of view actually taking place a year before those featuring Rachel’s investigations. Now, sure, I’ll concede that this probably isn’t a substantially more contrived resolution than the twist for which I praised Adrenaline, but the crucial difference there is that Anghelides actually managed to hold my attention, even in spite of that story’s being ever so slightly longer.

It also doesn’t help that, prose-wise, Approximate Time of Death really betrays its origins as the work of a first-time writer, with awkward and ill-constructed sentences aplenty. Add to that a wholly unselfconscious use of a clichéd “The villain confesses to their crimes while on camera” resolution, and you’re left with a bit of a mess, all told.

It’s hard for me to imagine that the last three stories of this collection will manage to get much worse than this, which is, in a way, reassuring, but it’s equally difficult for me to come up with too much to say about Approximate Time of Death. It’s not even bad in an offensive or interesting way, with its most profound sin being one of all-consuming tedium, but as we’ve observed many a time over the past one hundred reviews, that might actually be one of the worst possible outcomes.

8. Secret of the Black Planet by Lance Parkin

Much like Kate Orman, Lance Parkin has had a busy eighteen months or so in the lead-up to Re:Generations. After making quite the splash on impact with his critically acclaimed debut novel Just War, he went on to willingly shoulder the frankly insane task of assembling every Doctor Who story in existence into a single coherent timeline in A History of the Universe some four months later.

Since then, the man’s commitment to the vaunted “nightmare brief” has shown no signs of stopping, turning out the first and only multi-Doctor Missing Adventure and wrapping up the Doctor-led New Adventures with Cold Fusion and The Dying Days, respectively. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Parkin’s output in this period, however, is his ability to maintain a pretty consistent level of quality. I mean, I’d probably put The Dying Days as the weakest of his first three novels, but it’s by no means a bad piece of work, probably being on par with Orman’s own less Earth-shatteringly incredible books from this same era like Return of the Living Dad or SLEEPY.

Past this point, Parkin’s rate of output drops off considerably, with our next chance to discuss his work being some forty-seven books away when we get around to the co-authored Beige Planet Mars. As such, Secret of the Black Planet inevitably takes on a deeper importance than it might otherwise have when taken in isolation, closing off this initial flurry of Doctor Who-related writing from the author as it does.

Fortunately, it’s more than capable of supporting that extra weight, single-handedly pulling the anthology out of the brief rut in which it had found itself and offering a disturbingly prescient take on the perils of revisionist history.

To those who’ve been paying attention over the course of my past couple of reviews on Parkin’s novels, it shouldn’t exactly come as a surprise that he should adapt so readily to the themes of Re:Generations. More than any other author, Parkin’s oeuvre demonstrates a repeated engagement with the historicisation of Doctor Who, and by extension with the very mechanics of history itself. Even outside of the realms of fiction, what is a work like A History of the Universe if not the most potent literalisation of that theme?

Secret of the Black Planet, then, fits comfortably alongside all the books that came before it, building on the hints seeded in Second Chances and Heritage as to the Forrester family’s connection to Nelson Mandela, and the possibility that said connection was the product of considerable exaggeration and mythmaking through the centuries.

In fact, the use of the term “mythmaking” is strangely appropriate in this context, as Parkin’s story certainly feels of a piece with Shopping for Eternity, exhibiting a similar fascination with the idea of a media-manufactured Messiah, and consequently suffusing itself with a gloriously cynical and sharp-edged satirical tone.

To pick a particularly cutting and pertinent example, Parkin peppers the first half of the story with brief cutaways to a schlocky action film and the uproarious audience response, letting out choice bits of information through the main body of the text until it gradually becomes clear that the film is in fact purportedly based on the life and times of Mandela, complete with P. W. Botha in the role of a generic action movie antagonist.

On the face of it, it’s a wonderfully funny joke, but it also speaks to the wider existential horror at play within the story, and an instinctive revulsion at the idea of the cinematised and sanitised version of history coming to supplant the real thing, to the point where statues ostensibly built in Mandela’s memory actually bear the likeness of actor Troy Forrester, and the film can be remade just eight years after its initial release for the sole purpose of shoring up Forrester’s presidential campaign by cementing his connection to Mandela in the popular consciousness.

To say that these ideas have a strange timeliness in 2023 would be a huge understatement. Of course, perhaps the biggest gulf separating a contemporary reader from the context in which Secret of the Black Planet would have originally been read in May 1997 is the fact that Mandela has actually passed away by this time, and one can reasonably start sifting through the evidence of the ages to make a concrete determination of what Mandela’s “legacy” actually is.

Certainly, the notion that the activist and eventual statesman might end up somewhat sanitised and watered-down in the imagining of those in power would seem to be borne out by such events as his posthumous valorisation by Republican Senator Ted Cruz, of all people, conveniently glossing over minor trivialities like the American government’s continuous vetoing of any efforts by the United Nations to impose economic sanctions upon the South African government in the days of apartheid.

Even the conversations about the relationship between cinematic portraits of Mandela and historical fact seem particularly pointed when viewed with the knowledge of the controversy surrounding films like Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, which sparked similar discussions upon its eerily-timed release in late 2013, with the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory going so far as to “warn against accepting the movie as historically accurate.”

(Mind you, it’s not as if one is spoilt for choice when looking for films entitled Mandela contemporaneous to Re:Generations‘ release in 1997. October 1996 saw the release of Angus Gibson and Jo Menell’s Mandela: Son of Africa, Father of a Nation, which went on to secure an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary, while Sidney Poitier and Michael Caine assumed the title roles in Showtime’s Mandela and de Klerk some four months later.)

And the final crushing irony is that Troy’s brother Kent, despite trying his best to push back against the revisionism surrounding him, ultimately finds himself subsumed by it and transformed into a Mandela analogue in his own right, being imprisoned for twenty-seven years and becoming the subject of campaigns to secure his release.

History, it seems, is more often written by the Forresters than by the victors.

On a deeper level than the Mandela-connected elements, however, Secret of the Black Planet also feels prescient in its depiction of an Internet-dominated age in which the truth has become a somewhat mutable and flexible thing. While the world may not yet have quite caught up to Parkin’s pessimistic vision of a single corporation that has effectively placed a complete stranglehold upon individuals’ access to the Internet’s vast repositories of information, there were signs even in May 1997 that the “information superhighway” spoken of so glowingly by folks like Al Gore was due to be supplanted by a far more cynical kind of vision.

1994 saw the advent of a highly-publicised research programme into the prospect of digital libraries, with $24.4 million in funding from DARPA, NASA and the NSF. Among the research projects launched as a part of this initiative was one by Stanford University students Larry Page and Sergey Brin, eventually leading directly to the founding of Google and a fundamental shift in the way ordinary citizens accessed information. As such, Parkin’s unease over the commodification of online data serves as an effective snapshot of an Internet rapidly undergoing a profound transformation.

Mind you, things aren’t perfect, and Secret of the Black Planet could certainly be said to miss a trick in its handling of the racial aspects of all this. The people engaged in the rewriting of history are conspicuous in their Black identity, with the suggestion that Mandela has been recast as the originator of apartheid rather than its opponent seeming to stand as a rather paranoid invocation of all manner of fantasies about “reverse racism” against white people.

And if we’re being honest, this was something very much baked into Roz’s character from the time of Original Sin, with her hatred of aliens serving to play on the dramatic irony of a Black woman acting in a xenophobic and racist manner.

Thankfully, those elements were eventually tempered by later, more interesting development on the part of writers like Ben Aaronovitch and Kate Orman, but this is probably the most salient point to concede some of the issues that do tend to arise when your pool of writers is so overwhelmingly white, as Doctor Who‘s has been for most of its history. It’s a minor flaw, and doesn’t necessarily undermine the good ideas on display in this story and the collection in which it’s housed, but it is present nevertheless. Still, Secret of the Black Planet is largely a welcome return to form from Re:Generations, and a decent enough note for Parkin to temporarily bow out on.

9. Rescue Mission by Paul Leonard

I’ve spoken in the past about the rather weird place that Paul Leonard occupies in the tapestry of my opinions on Virgin’s pool of writers. More often than not, I find myself thinking that his novels begin with a rather excellent set of ideas, before gradually losing steam or changing to become something far more banal and uninteresting.

In fact, the only occasion on which I didn’t really get this sensation was in reading his most recent contribution to the Missing Adventures, Speed of Flight, which I lauded as his most consistent book so far. While that meant it largely avoided the crushing lows of the denouements of stories like Dancing the Code or Toy Soldiers, though, it also meant that there was never anything particularly gripping to begin with, either. Still, I found it hard to get too cut up about it, mainly due to its relative brevity when compared to the overlong and tedious pseudo-epics with which it was surrounded.

The logical conclusion, then, might be to surmise that Leonard’s ideas work best in small doses, and that he would likely be an author particularly well-served by the medium of the short story. Having read Rescue Mission, the writer’s final solo contribution to Virgin, I’m inclined to say that this conclusion was, by a strange stroke of good luck, the correct one.

It would certainly be an exaggeration to say that this was my favourite story in the collection, but as you might be led to expect from the rather barebones title, Rescue Mission has a very clear sense of purpose and drive underpinning it, opting to deliver readers a short, compact package comprised of everything one has come to expect from Leonard’s signature style. That style may not always lend itself to the deepest of ideas, but it does allow for the sustenance of a certain amount of momentum throughout the story’s twenty-three page length.

At its heart, the Paul Leonard novel that Rescue Mission most clearly resembles is probably something like Toy Soldiers, but the differences are rather telling. As with that earlier book, Leonard is betting on his ability to communicate the sense of sheer, inherent wrongness that accompanies a situation in which children find themselves forced into acts of violence.

And, fair play to him, there were momentary glimmers within Toy Soldiers where the boons of that ability shone through, with the sections unfolding in the aftermath of World War One proving particularly moving. It was only really once the action shifted to Q’ell, with its hazily-defined, dime-a-dozen alien conflict, that the cracks really started to show in Leonard’s portrait of the issue of child soldiery.

In contrast, Rescue Mission consciously scales back its ambitions, focusing in on a single pair of siblings rather than trying to take in every possible facet of a complex social issue. By and large, this is a decision which pays off in spades, and the steadfast refusal of Abe to give up on his childlike innocence, even in the face of the overwhelming horror with which he is surrounded, manages to be far more affecting than anything in the earlier novel.

The most simplistic characterisation of Abe’s arc would be to make the observation that he fundamentally misunderstands the kind of story he’s in, believing himself to be in a work of children’s literature when he’s actually in something far darker. Rescue Mission certainly provides ample evidence for that conclusion, with the titular mission hewing to a rather familiar “teenage protagonist bands together with his friends to go on an adventure” structure before undergoing the sharpest possible left turn once our hapless heroes arrive on the chief antagonist’s island, only to be near-instantaneously slaughtered.

But this fails to consider the fact that Leonard is actually doing something far more shrewd here. It’s hardly controversial to assert that a fair chunk of children’s literature – and especially children’s adventure literature – is principally concerned with the process of growing up. Abe, then, takes that approach to a rather gloomy and grim extreme, serving as an archetypal children’s literature protagonist whose chief failing lies in his steadfast refusal to have that revelatory moment, right up until the moment of his death and the end of his script.

Particularly devastating is the change of gears at the last minute, as it turns out that only Abe and Callie’s distant baronial Forrester relatives are capable of launching a truly effective rescue mission thanks to their privilege and wealth affording them the ability to freely operate within the Empire’s power structures. Moreover, even Callie’s eventual liberty doesn’t protect her from the media circus seeking to reduce her to a sensationalist symbol with which to grab the attention of audiences.

This skepticism of stories has, as you’ve probably noticed, quietly become a recurring theme for Re:Generations, particularly in its back half. Really, the only story since Burning Bright not to demonstrate this sort of profound unease with the reduction of human beings down to a string of flattened narrative beats was Approximate Time of Death, and I don’t think it’s entirely a coincidence that that’s the story I singled out as the collection’s worst.